What exactly is the Belt and Road Initiative and how could it transform China’s economy?

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

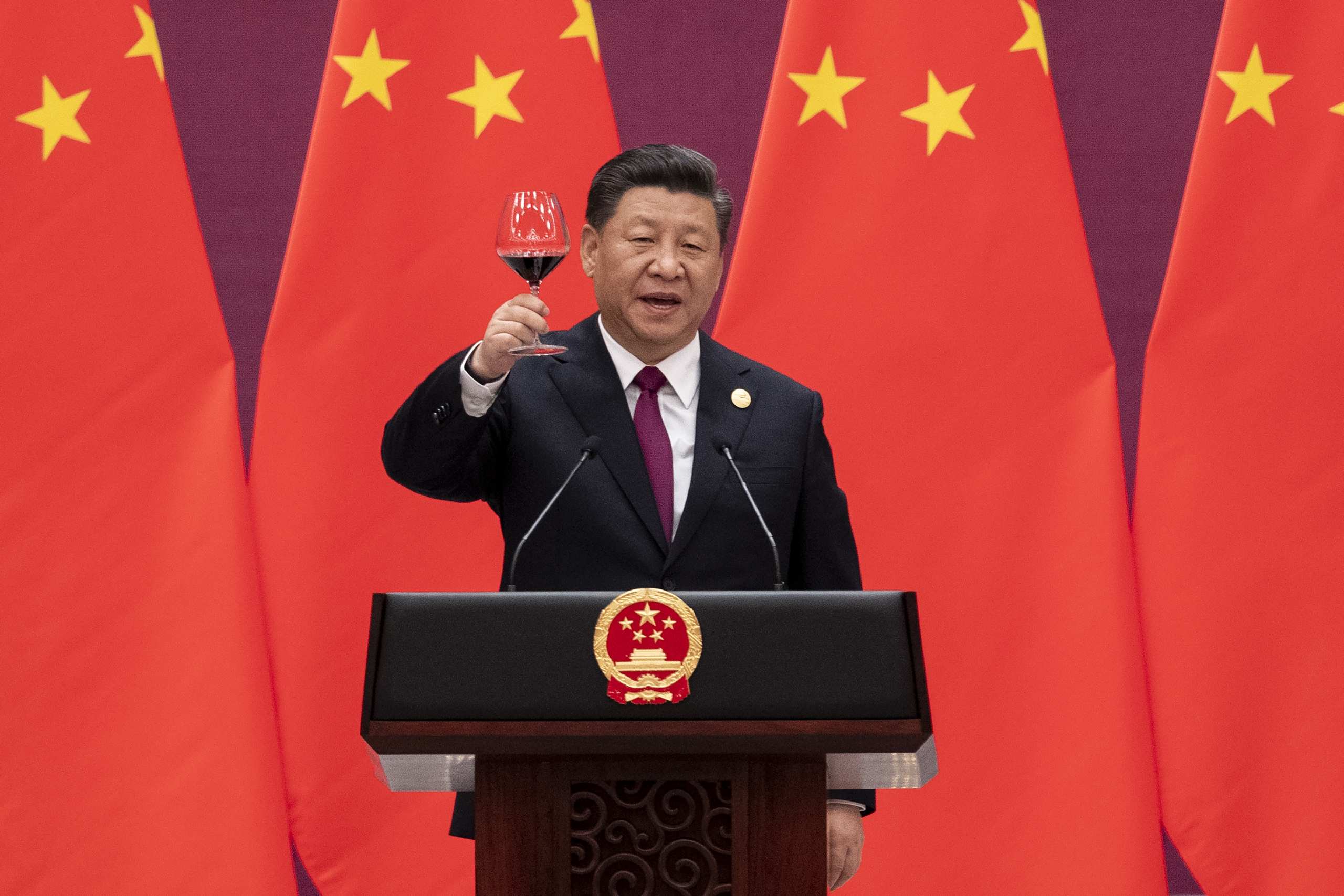

Since 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China’s President Xi Jinping has been reshaping trade in the region, with ripple effects throughout the global economy. The ambitious plan looks to simultaneously build up China’s historically underdeveloped neighbors while expanding the potential customer base for China’s products.

On the surface, the BRI represents an embrace of free trade by China. However, critics have also argued that the initiative represents a political and economic overreach by the country.

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

The BRI has been called “one of the most ambitious infrastructure investment efforts in history,” an acknowledgement of just how far-reaching the Chinese government’s plan is. It’s also considered the crown jewel of President Xi’s economic vision for the country, one he has championed while seeking to build China’s global trade relationships.

When launched in 2013, the economic initiative was initially known as the “One Belt, One Road” (y? dài y? lù) strategy. However, the “strategy” terminology was soon dropped over concerns it would induce suspicions in other countries and the official name was changed to the Belt and Road Initiative in 2016.

However, Chinese media still often refers to the initiative as One Belt, One Road and it is often abbreviated as OBOR.

With an estimated cost of US$1 trillion, the BRI aims to closely link China’s economy with those of the 71 other countries. China would fund construction and infrastructure projects in nations across multiple continents, as well as in regions within China where development has historically been lacking.

The BRI directly benefits China by expanding opportunities for Chinese firms to do business. Multiple African countries have welcomed the development and money that these firms bring.

The ancillary benefit of funding projects in other countries is helping those countries develop, not only structurally, but economically as well. Increasing the number of developed countries means China can grow its customer base. If free trade expands globally as a result, Xi’s aims for China will have been realized.

Though the economic goals appear straightforward, the specific parameters and trade agreements that fall under the rubric of the BRI are less clearly defined. That’s because, as stated by CNN in 2017, “Chinese officials tend to mention it regardless of what they’re trying to promote.”

Criticisms of the BRI

The BRI’s ambitious international outreach has drawn criticism, both for the harm it purportedly does to other countries, and for its internal weaknesses.

In 2018, it was reported that of the thousands of projects initiated under the BRI, hundreds had run into substantial difficulties. Malaysia, for example, has canceled major, China-backed projects due to an accumulation of debt.

While China provides loans to countries that take on these projects, many of the poorer countries involved are finding themselves accumulating greater debt to keep up. Some critics have suggested that putting other countries in debt to China is a feature of the BRI, not a bug.

Other critics of the initiative have cited a lack of return on investment as proof the BRI will, in the long term, be an economic and political failure for Xi.

Writing for Foreign Policy in 2018, Tanner Greer, a Taiwan-based strategist, argued, “Investment decisions often seem to be driven by geopolitical needs instead of sound financial sense.”

Taiwan, alongside Hong Kong and Macau is a state that operates under the one country, two systems administration policy.

The two Silk Roads of the BRI

Most explanations of the details of the BRI fall back on the same analogy: the Silk Road.

The BRI is actually two different projects: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The former is made up of trade routes on land, while the latter are the sea trade routes.

The original Silk Road (or Silk Route) was a collection of trade routes between China and Western nations that existed for nearly two millennia, until the Ottoman Empire closed off trade with China in the 15th century. These trade routes not only allowed goods to spread from nation to nation, but culture as well.

Embracing free trade

The BRI is vital to realizing Xi’s overall foreign policy.

In 2017, while speaking to the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, China’s president laid out his vision for a “community of common destiny.”

Though Xi was not the first to use that expression, it succinctly sums up his larger goals for China.

This “community of common destiny” defines a global economy in which interests and responsibilities are aligned across borders. That ethos essentially defines free trade agreements, which have been embraced by many Western nations.

The original North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was an agreement between Mexico, Canada and the US, signed in 1993 by former President Bill Clinton. At the time, it was the largest free trade agreement in the world.

NAFTA allowed for easier trade between the three countries, which in turn gave the group greater bargaining power on the global stage.

President Donald Trump has frequently criticized NAFTA, claiming it creates an unfair trade imbalance for the US in relation to Mexico and Canada. In January 2020, his administration signed a new trade deal known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which keeps much of NAFTA intact, with some changes.

[article_ad]

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters here!

Comments ()