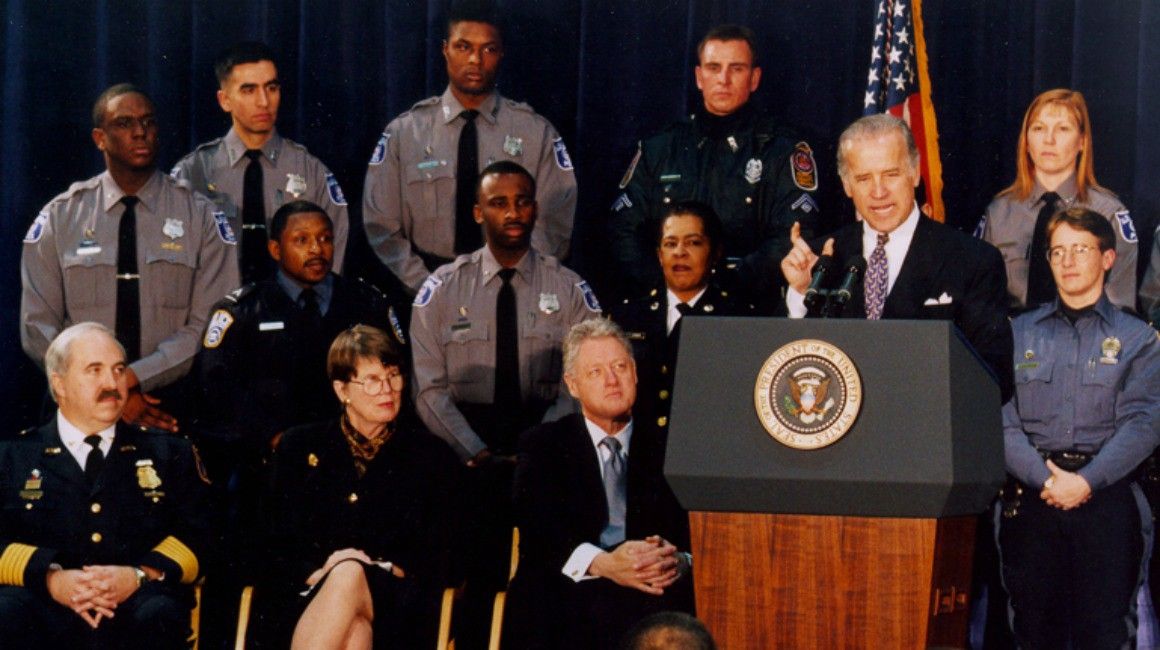

What you should know about Joe Biden’s 1994 crime bill

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

On September 13, 1994, then-President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, often referred to today as simply the 1994 crime bill.

The bill was authored and championed by then-Senator Joe Biden and sought to address a wave of crime in America, which had been a bipartisan concern for many preceding decades.

Initially a legislative victory for Biden, the bill is now a liability in his campaign to become president. Many critics claim that it has led to mass incarceration and has helped create the modern police state, which has most dramatically affected communities of color. The actual effects of the bill continue to be debated, but to fully understand it, it’s important to understand the context in which it was created.

Crime in America

From 1960 to 1990, crime rates in the United States steadily climbed in almost all categories.

In 1960, there were roughly 1,887 crimes per 100,000 people. By 1990, those numbers had more than tripled to just over 5,820 crimes per 100,000 people.

Even when accounting for population growth, the number of rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults in 1990 were more than four times greater than in 1960. Other crimes like car theft and burglary didn’t increase by quite that rate, but were still more than twice as common.

The one semi-outlier was murder. Though the murder rate rose to a high of 10.2 per 100,000 people in 1980, by 1990, it had dropped to 9.4, still nearly double the 1960 rate of 5.1.

At the beginning of the 90s, Washington, DC in particular was a hotbed of violent crime, with headlines calling it the “murder capital” of the US. Nationally, it was common to read regular headlines about the high crime rates in cities as diverse as New York City, Colorado Springs, Chicago, Seattle and Santa Ana, California.

A 1991 report by the US Department of Justice, which found that crime rates had fluctuated throughout the 80s, noted, “Blacks are more likely than whites to be victims of a violent crime … Blacks experience higher rates of rape, robbery, and aggravated assault, but whites have a higher victimization rate for simple assault.”

Those statistics may be why the 1994 crime bill had so much support in the black community at the time. Numerous black mayors backed it and dozens of pastors from the community signed a letter in favor of it.

Now, however, the crime bill is seen as a scourge for the black community. So what happened?

What was the 1994 crime bill?

Though the reliability of crime statistics are a perennial topic of debate, it was clear that crime was a major concern in October 1993 when Biden introduced the first version of what would become a US$30.2 billion bill.

As with all bills, the 1994 crime bill, sponsored by Democratic Representative Jack Brooks, went through the Senate and the House of Representatives multiple times before it was finally passed by both chambers. Nearly a year after its introduction, Clinton signed the bill into law.

The crime bill was a multi-faceted attempt to address violent crime in the country, largely by expanding or increasing federal laws. It was broken into dozens of sections (or Titles) and hundreds of subsections. It covered a range of topics from prison and drug policies to the prosecution of computer crime and child pornography.

The bill provided funding for 100,000 new police officers across the country, while also setting aside US$9.7 billion for new prisons and an additional US$6.1 billion for drug and crime prevention programs.

Much of the modern controversy around the bill surrounds the view that it has led to mass incarceration, especially among people of color. The bill has also led more defendants to take plea deals and accept prison time without a trial to avoid a much more severe punishment if found guilty, even when innocent.

While the bill specifically increased sentences for hate crimes, terrorism and violent crimes, the bill also set aside funding grants to encourage states to toughen their sentencing laws. The ACLU has argued that those grants indirectly led to an increase in incarcerations, even in non-federal prisons.

Despite the law’s modern unfavorability, there are aspects of the law that do remain popular among Democrats.

The crime bill included the Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act, or the Federal Assault Weapons Ban. The law prohibited “the manufacture, transfer, or possession of a semiautomatic assault weapon.”

However, the ban expired in 2004 and lawmakers still debate its effectiveness. Nonetheless, many gun control advocates would like to see a new version of the ban enacted.

The bill also contained the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). The VAWA provided nearly US$2 billion to combat domestic violence in the US. Biden has regularly touted that bill as one of his greatest political achievements and has vowed to expand the VAWA as president.

Who voted for the crime bill?

The bill passed in the House of Representatives by a vote of 235 to 195, with 188 Democrats, 46 Republicans, and one Independent voting “aye” in favor of it. Against the bill were 64 Democrats and 131 Republicans. Five members of the house – four Democrats and one Republican – did not vote.

Considering that many liberal voters now disapprove of the bill, it is notable that only five of the House Democrats who voted against the bill remain in office: Representatives Maxine Waters, John Lewis, Jerrold Nadler, Peter DeFazio and Robert Scott. The Democrats who opposed the bill at the time called it too “simplistic” in its approach to crime and objected to the increases in prison sentencing.

Of the Democrats who voted for the bill, three make up the current House leadership: Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer and Majority Whip Jim Clyburn. Neither of the current Republican House leaders – Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and Minority Whip Steve Scalise – were in the House in 1994.

In the Senate, the bill passed with the support of 54 Democrats and seven Republicans. The opposition to the vote included two Democrats and 36 Republicans, with one Republican not voting.

Of the two Senate Democrats who voted against the bill in 1994, one is no longer in office, and the other, Richard Shelby of Alabama, switched to the Republican Party later that year.

Republican Senator Mitch McConnell, the current Senate Majority Leader, voted against the final bill. Democratic Senators Chuck Schumer, the Minority Leader, and Dick Durbin, the Minority Whip, voted for the bill, though both were then members of the House.

As reported in the Baltimore Sun at the time, Republicans who opposed the bill did so largely because they felt that it was “not harsh enough,” while others balked at the price tag. An even bigger hurdle was the assault weapons ban. Nonetheless, the bill survived the contentious congressional battle.

Addressing the underlying issues of crime

Biden’s main rival for the presidential nomination in 2020, Senator Bernie Sanders, was the one Independent member of the House in 1994 who voted for the bill. However, his support was hardly wholehearted.

In an April 1994 speech on the House floor, Sanders denounced it as a bill he believed would lead to mass incarcerations and didn’t address underlying problems.

“A society which neglects, which oppresses, and which disdains a very significant part of its population, which leaves them hungry, impoverished, unemployed, uneducated, and utterly without hope, will, through cause and effect, create a population which is bitter, which is anger, which is violent, and a society which is crime-ridden.”

This contrasts with a speech Biden gave on the Senate floor on November 18, 1993, in which he stated about criminals, “I don’t want to ask, ‘What made them do this?’ They must be taken off the street.” Biden argued that the country needed to be tough on “predator” criminals, while acknowledging the many at-risk children in America.

“Unless we do something about that cadre of young people, tens of thousands of them born out of wedlock, without parents, without supervision, without any structure, without any conscience developing … because they literally have not been socialized. They literally have not had an opportunity. We should focus on them now. Not out of a liberal instinct for ‘love, brother and humanity’ – although I think that’s a good instinct – but for simple pragmatic reasons: if we don’t, they will, or a portion of them will, become the predators 15 years from now.”

Biden also seemed to accept that increased incarcerations wouldn’t solve the underlying issue. “It’s a sad commentary on society. We have no choice but to take them out of society. And the truth is, we don’t very well know how to rehabilitate them at that point. That’s the sad truth.”

Sanders’ “aye” vote was due to the inclusion of the VAWA, which he said he “vigorously support[ed]” despite his problems with the rest of the crime bill.

What have been the results of the crime bill?

All these years later, Biden has said that the crime bill, even if it had some flaws, effectively cut violent crime in America in half. Biden is correct that in the over two decades since the bill passed, violent crime has decreased dramatically. The question, though, is whether that decrease actually has anything to do with the crime bill.

Meanwhile, the bill’s critics point to the disparity of minorities in prison. In 2015, there were 2.2 million people in American prisons (21% of prisoners globally), with African Americans incarcerated at five times the rate of white Americans. Together, African Americans and Hispanics make up 32% of the country’s population, but 56% of the prison population.

Then there is the fact that one in every three black males in America will end up in prison at some point in their lives. Such racial disparity is said to create a cycle in which people of color are invariably cycled in and out of the prison system.

Did the crime bill really have an effect?

From the moment the bill passed, the effectiveness of the crime bill was in question.

In 1994, critics wondered if 100,000 new police officers spread throughout the country would make much of a difference. There were also doubts about many of the new programs introduced in the bill. The bill was viewed by some as nothing more than a placebo to convince the country that the government was addressing crime.

More recently, Fordham University law professor John Pfaff took to Twitter to argue against two common beliefs about the bill: that it led to mass incarceration and that it helped reduce crime. As explained by Business Insider, Pfaff was reacting to a recent confrontation between Clinton and Black Lives Matter advocates over the law. (Clinton had previously said that the crime bill was flawed.)

As Pfaff states, incarceration rates in the US had already been on a dramatic upswing since the mid-80s due to previous laws passed under the Reagan administration. Following President Barack Obama’s first term, these rates have been declining, hitting a two-decade low in 2016.

Similarly, Pfaff flat out dismisses the view that the crime bill was responsible for the decrease in crime, specifically because it only directly affected federal law. As it turns out, 1990 was essentially a peak for crime in the country, and by the time the bill was passed, crime rates were already dropping.

Pfaff’s refutation of both sides of the debate relies on the same argument: federal laws were less impactful on crime reduction and incarceration rates than state laws.

However, as the ACLU has argued about the grants, critics believe the standard set by the crime bill – and the tough on crime tone set by the Democrats – helped influence crime laws on the state level.

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Sign up for daily news briefs from The Millennial Source here!

Comments ()