US scientists reportedly have made a fusion energy scientific breakthrough

Since the 1950s, scientists and researchers have struggled to prove that fusion can release more energy than it takes in.

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

Since the 1950s, scientists and researchers have struggled to prove that fusion can release more energy than it takes in. Fusion is a process that combines two atoms using extreme heat to produce bursts of energy. It's what powers the sun and stars, and fusion fans say it could one day provide limitless cheap energy.

Fusion power investment surged recently because of pressing climate concerns. According to the Fusion Industry Association, fusion companies raised around US$2.83 billion over the last year, bringing the sector's total private investment to almost US$4.9 billion.

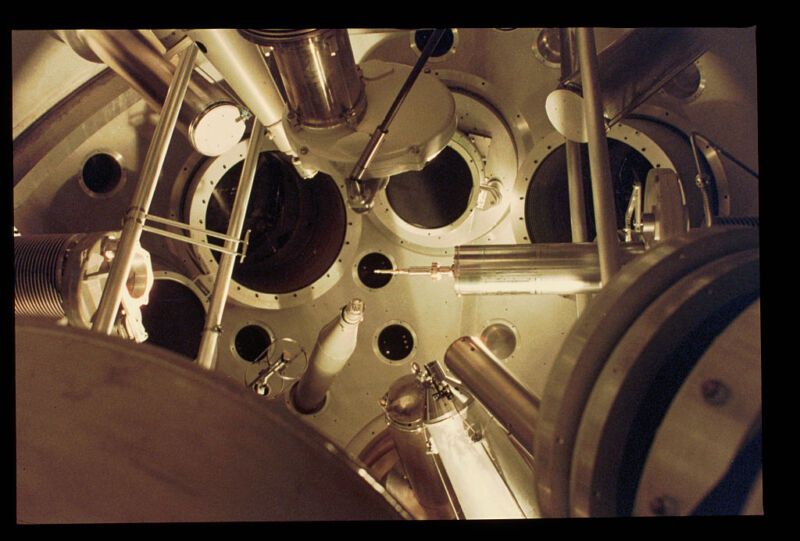

Now, US government scientists in California have reportedly made a major breakthrough in pursuing a "near-limitless, safe, clean" energy source by achieving a net energy gain in a fusion reaction for the first time in history. An announcement Tuesday is expected to confirm that researchers have generated 1.2 times more energy than consumed using lasers to create a fusion reaction.

For decades, the idea that fusion tech could be used commercially as an energy source has been only so many years away, according to the scientists working on it. But, as we can see, this breakthrough is just a small step in clean power development. But, if we can successfully harness the tech to create clean energy, it could provide a reliable, abundant alternative to fossil fuels and conventional nuclear energy.

Key comments:

"It's one of the biggest results of science in the past 20-30 years," said Gianluca Sarri, a professor at Queen's University Belfast.

"Fusion has the potential to provide a near-limitless, safe, clean, source of carbon-free baseload energy," said Dr Robbie Scott, who participated in the research, from the Science and Technology Facilities Council's Central Laser Facility Plasma Physics Group.

"Anyone working in fusion would be quick to point out that there is still a long way to go from demonstrating energy gain to getting to wall-plug efficiency where the energy coming from a fusion reactor exceeds its electrical energy input required to run the reactor," said Jeremy Chittenden, professor of plasma physics at Imperial College London.

"Initial diagnostic data suggests another successful experiment at the National Ignition Facility. However, the exact yield is still being determined, and we can't confirm that it is over the threshold at this time," said the US Department of Energy, suggesting reports not get ahead of the official announcement on Tuesday. "That analysis is in process, so publishing the information . . . before that process is complete would be inaccurate."

Comments ()