At 16, writer, illustrator and digital artist Sophia Hotung was diagnosed with the first of many chronic autoimmune illnesses. Fast forward a decade, and by the time she was 26, her condition had become too debilitating to continue working.

Welcome to the new Human Stories series by TMS, where we get to know Hong Kong through its many different faces. This month, we're speaking with Sophia Hotung, the illustrator of The Hong Konger and author of "The Hong Konger Anthology" and "The Heist of Hooded Light."

At 16, writer, illustrator and digital artist Sophia Hotung was diagnosed with the first of many chronic autoimmune illnesses. Fast forward a decade, and by the time she was 26, her condition had become too debilitating to continue working the corporate jobs she had diligently pursued since graduating from Barnard College at Columbia in New York City.

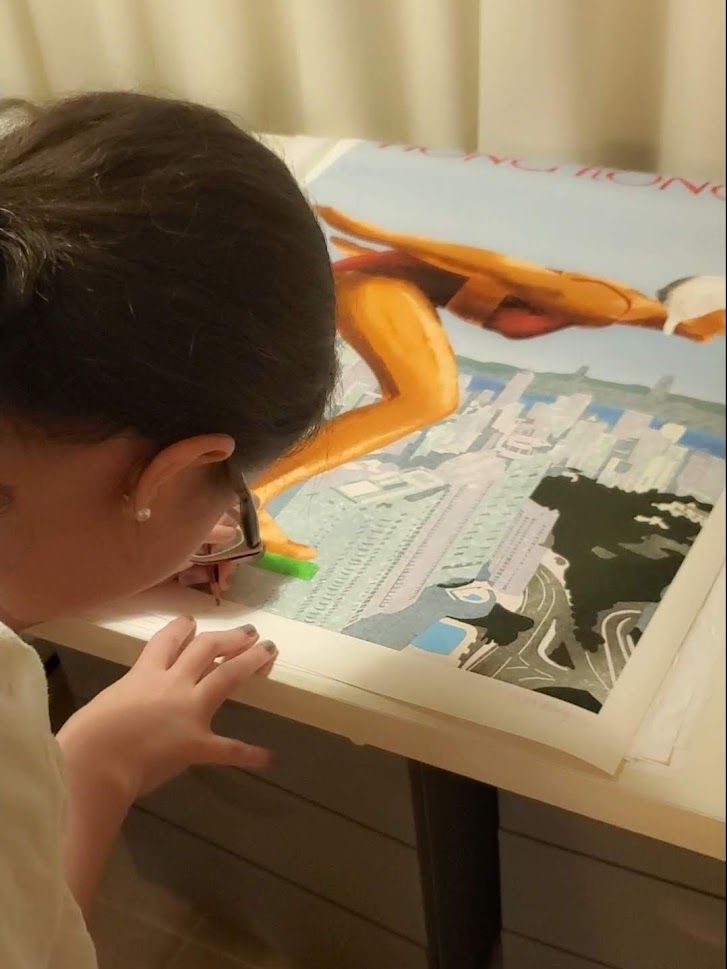

It was when she was at her lowest point of being "hopeless" when her mother gifted her an iPad. Being bedridden, Hotung downloaded a drawing app called Procreate to pass the time.

"She gave me an iPad, and the iPad became a way for me to have agency again and have interest in things again," Hotung explains.

While playing around with the app, Hotung was inspired to do a Hong Kong version of the famous The New Yorker magazine covers. Since then, her life has taken a new path as her artworks have gained traction, affording her opportunities to work with charities, discuss her now-IB-curriculum book with high schoolers and even create art with robots.

TMS sat down with Hotung to discuss her journey of developing a career out of passion, reconfiguring her self-worth, accepting and understanding disability and everything in between.

In the beginning

Hotung's love of art goes back to when she was just a toddler. Her mom, a management consultant, started an art school in 1996 called Kids' Gallery because she wanted to spend more time with her children while still working.

"I spent most of my life there. When kids would take the school bus home, I would take the school bus to Kids' Gallery," she recalls. "And my sister and I would spend almost every day after school doing art classes."

These classes also exposed Hotung to many different creative endeavors. "Sometimes if a class had like one other kid in it, they'd put us in there to make it more crowded and popular, which was great because I'd end up doing all this stuff I wouldn't have done otherwise, like Chinese brush painting or musical theater, even though I didn't like performing in the beginning," she remembers. "So it opened my eyes up to a lot of art that I wouldn't have picked by myself."

But another critical experience during this time for Hotung was learning to enjoy art for the sake of art rather than pursuing it competitively.

"The other thing was I was never good at it. Like, I was never the best kid in the class. I didn't get the lead roles in shows; I didn't get my art up in the exhibition, but I was just always there having a good time.

"And I think, especially being a Hong Kong student, where everything is graded and everything is on a ranking, to have a place as a kid where I could do what I wanted and there was no pressure – it didn't even occur to me that I would be ranked or graded on it – was very healthy, and I think a lot of kids don't have that. And I was very fortunate to have that."

So, art began as a safe space and, throughout her life, has become a refuge for the stresses of her career, dealing with her chronic illness and everything else.

"So even when, you know, I'm still a Hong Kong kid – I had to go to a good university, I had to get good grades – I always knew that if I got stressed out, I could do art. And that was an environment for me where I knew I wasn't good; I didn't have to be good."

Even if art isn't at the top of the list when it comes to traditional education, especially growing up in Asian culture and bound for the university track, Hotung emphasizes its importance in all areas of life.

"It's so important to have art like you would have language and maths because art permeates everything," Hotung says. "Even if you work in a corporate field, you need someone to communicate ideas. You need someone who's a good storyteller who can capture something visually. So art is important in industry. Art is important for an intrapersonal link to yourself to heal, for art therapy, that sort of stuff. I think in every single subject you can teach art, and art has an application.

"So when it comes to educating the youth of tomorrow, I think emphasizing that art isn't a waste of time is important because there is a mentality that you can't grade it; you can't get a certificate on it. There's no stats like in sports. It's still important. And it's so important to have things in life that can't be quantified because that's usually where all the wishy washy mental health goodies like healing comes from."

Transitioning from a corporate career to a passion project

Although Hotung had plenty of exposure to art growing up, there did come a time when the pressure hit to go to university and forge a "successful" career.

Hotung recalls her university days when the three careers everyone wanted to get into were software engineer, investment banker or management consultant. But, while studying in the US, Hotung had been pursuing an English degree. Aside from her interest in it, she was good at it, and that pressure to excel was always hovering in the background.

"So I was like, I was going to get all A's in English rather than B's and C's in Econ. … And then towards the end of my junior year, I started to feel real pressure about getting a job," Hotung remembers. "All my friends were getting return offers from summer internships at McKinsey, at like Goldman Sachs, and I felt so left out.

"And I couldn't code, and I couldn't do math, so I had to be a management consultant," Hotung jokingly admits. "And I just really abandoned English. I really didn't want to tell people I did English because I was so ashamed that it wasn't successful or corporate enough. Even though I really loved writing. I loved English, I loved reading."

So, she headed down the track that rings a bell to many, no matter in New York or Hong Kong – superdays, meet and greets and business cards endlessly exchanged.

In her days as a crisis communications manager, Hotung's mind was occupied by the temptation to leave and focus on writing, but she never did for fear of abandoning the practical benefits that we are so accustomed to equating as the golden ticket to a successful life. Instead, when the temptation would arise, she'd talk herself back from the ledge, reminding herself that she was on a good track or that she'd be better off waiting for more stability.

So, why would someone leave behind job security, a good salary and solid connections to pursue a passion project that might not guarantee any of these things?

As life often turns out, it's not always within our control after all.

"When I tell people, 'Oh yeah, I moved from a corporate career to being an artist,' they're like, 'Wow, that's so brave. I could never do that.' And honestly, it didn't require any bravery because I didn't have a choice. …

"And it's scary – when you have a really good salary on the table, when you have connections on the table, when you have security on the table – to leave, not know if you're going to get it back and not know if you going to succeed at your artistic career. So I get that. That's incredibly scary," Hotung admits.

But, in Hotung's case, becoming more ill and unable to work the way she used to ended up forcing her hand.

"Sometimes I joke around, but being sick was the best thing that happened to me because it really enabled me to do what I love to do," Hotung says. "And that's not something that a lot of people have the privilege of."

Hotung relapsed in her condition in 2017 due to her chronic illnesses. By 2021, she had become bedridden, and Hotung started getting restless.

Even though she had previously abandoned her pursuit of art and English during her hustle days of establishing a career, it had found a way to slip back into her life. Or perhaps, Hotung managed to find a natural way for this passion to become her life again.

What it means to be valuable

As Hotung's body fought a war against itself, she became sicker and sicker, eventually unable to work. With this came anxiety, depression and feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness. It became clear that the building bricks of her identity had to be reordered.

"I really, really focused my whole identity on being a hard worker and being someone that people thought was productive and smart and nice and just a very likable, hard working person," Hotung explains. "And when I realized I couldn't work anymore, I didn't know what to do because my whole value system was 'I'm only valuable if I'm working.'"

Especially as a young person with an Asian upbringing, the pressure to be a "good return on investment" for her parents compounded with the stress of simply figuring out who she is.

The idea that you have to be productive to be valuable has become so ingrained in society that we now have a name for it – "hustle culture." Proponents of this ideology champion working constantly, and anything else is considered lazy and looked down on.

"That's not a unique thing for many Hong Kong girls to think. I think a lot of us have pressure – and boys – everyone has pressure to deliver or be a good return on investment for your parents and stuff like that," Hotung points out. "And when you're suddenly not a good return on investment, when you're 25 and living at home and have no money, it's really hard to find value in yourself or think at least I'm nice."

For Hotung and many others, this was something that needed to be unlearned.

In her specific circumstances, she had to acknowledge that her chronic illnesses were no longer something she could brush off. It was OK to prioritize getting better, and doing that doesn't diminish her value at all.

"It's really a process, and I'm still getting better slowly, but I think I really had to rethink what disability is," Hotung says. "When you're not disabled, it's easy to either pity disabled people or secretly be quite judgmental about them and think, 'Oh, they're so lazy.' Or 'Oh, they're attention seeking.' And so I had to really tell myself, 'You're not attention seeking. This is a real problem you have. You're still a valuable person. You don't need to die to be productive or to stop being a burden.'...

"My priorities now are: getting better, but not so that I can be useful again to someone – getting better just for the sake of getting better and having value just for the sake of having value."

At the same time, she is weary of ever being seen as an "inspiring" figure.

Hotung points out that the way disabled people are celebrated tends to ignore their disability. Praise is given to those that fight against their disabilities and overexert themselves in pursuit of success.

"It shows disabled people that they are only valuable when they are not taking care of themselves, when they're pushing themselves, when they're doing something absolutely out of the ordinary for a disabled person," Hotung explains.

She reminds us of the disabled people who might be stuck in bed, not producing anything and feeling terrible for not living life according to a non-disabled person's (and society's) standards.

"So it's difficult to have those conversations because everyone who says it means well, and I really appreciate the message," Hotung expresses. "But at the same time, I try to say like, 'Let's rethink how we talk about inspiration because to encourage people to be unhealthy and that they're only valuable when they're unhealthy is unhealthy.'"

Finding a new path and creating organically

So, it stands to reason that Hotung found both refuge and productivity in her old love of art, writing and creative pursuits while she was ill and playing around on the iPad her mother gave her for Christmas. And she happened also to find a new successful career along the way.

"I started creating joke sort of artworks for my friends," Hotung says. "One of those things was called The Hong Konger. People liked it more than I thought they would, and so I kept making more and more and more to the point where people bought it and bought prints of it and bought the book I made of it.

"And now I've accidentally become an artist through The Hong Konger and have been able to do other things like write new books and make new art. And it's a way for me to be chronically ill and prioritize being chronically ill and getting treatment while also being able to make my own money and support myself, which has always been a concern for me."

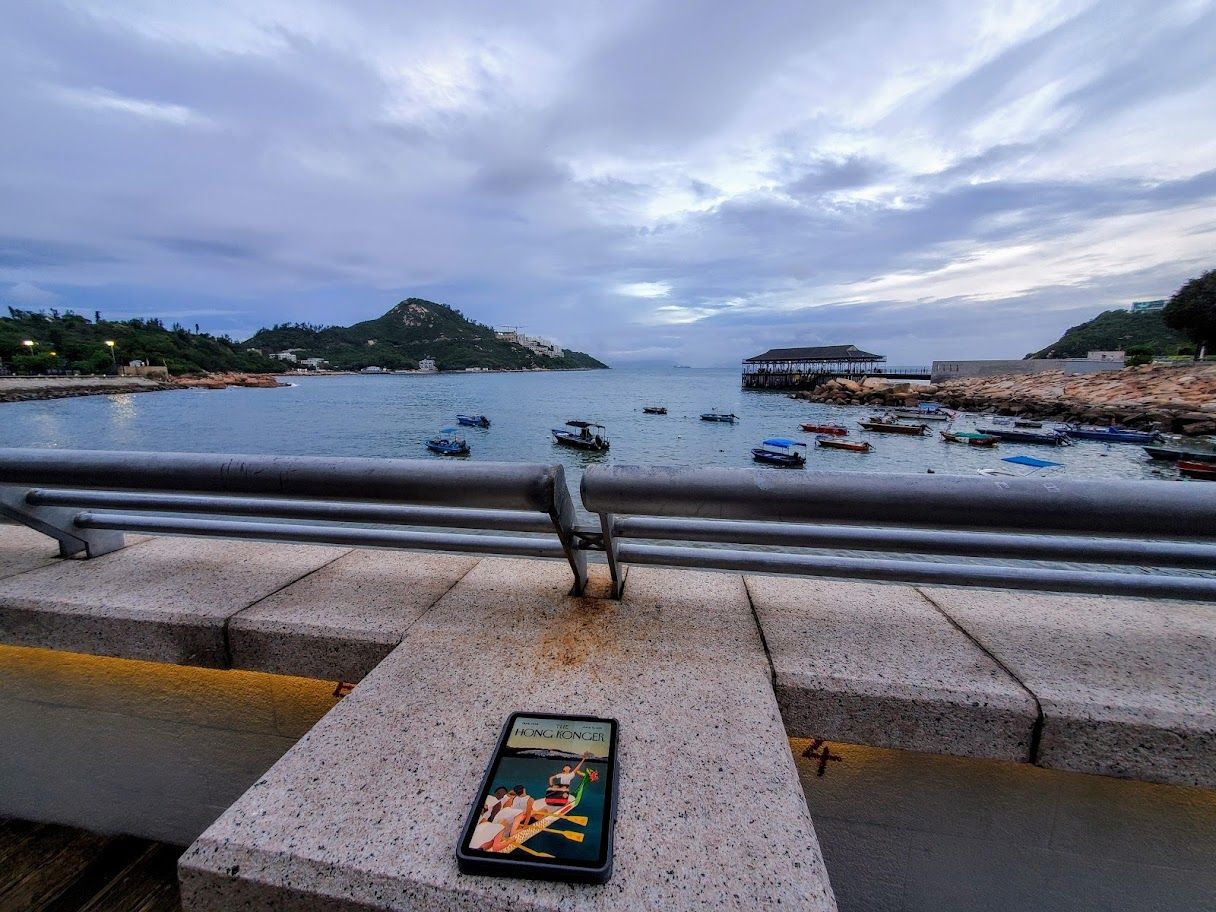

The Hong Konger collection subverts the famous covers of The New Yorker magazine that are known to be charged with a deeper story or meaning. Colored with Hong Kong charm and unmistakable memories, The Hong Konger eternalizes the city's quirks in clever illustrations.

For instance, inspired by the September 5, 1942 cover of The New Yorker that shows military factory workers during lunchtime, Hotung transforms that into a Domestic Workers' Day off on the Circular Pedestrian Bridge in Hong Kong's Causeway Bay.

Becoming an "accidental" artist was still a trek that required risk and putting herself out there. Once people showed interest in The Hong Konger pieces, she decided to sell them. Investing about HK$1,500 each to print and frame the covers, Hotung had high hopes when she sent them out to so many people that had shown interest in buying them.

"And the first email reply I got was, 'I think there's a typo. It says HK$8,000.' And I was like, 'No, it's meant to!' And they were like, 'Oh, well, that's far too expensive. Never mind.' And I just thought, 'Oh my God, I've invested so much money and I don't know what to do with all these prints.'"

So, she bet on herself once more by applying to enter Hong Kong's Art Next Expo. That was really a turning point for her as a professional artist. She sold a few pieces at the first Expo, more at the next, and expanded her size offerings, so there were smaller, less expensive prints available for collectors. And from there, word got around.

"Actually now when I'm way out of my depth and I'm thinking, 'Oh my God, I've really, really buried myself in a hole.' I can remember that I felt that on a smaller scale before," she says.

Next came more projects and books – even working on an art NFT with Sophia, the AI robot.

The Hong Konger Anthology, Hotung's book of 70 The Hong Konger prints and satirical poems, celebrates Hong Kong's unique characters and guarantees a familiar face smiling back.

Coping with criticism

As Hotung was creating the book, though, not everyone was appreciative.

"I got a lot of emails from people saying, 'You shouldn't be doing this. You're not a true Chinese person,' because I'm Eurasian. And it was difficult for me to not feel imposter syndrome or feel like I was appropriating Hong Kong culture, even though I'm from Hong Kong," Sophia says.

Hotung is Eurasian, but her experience has been unique from others in that she doesn't have one Asian parent and another European. Both of her parents are also Eurasian – her dad is American-Hong Konger, and her mother is English-Shanghainese. So, she spent time between Hong Kong and the UK as a child. But she's always felt most at home in Hong Kong.

Even so, she admits that she's no stranger to feeling like an outsider. Growing up without speaking Cantonese "properly" or being able to enjoy Cantonese and Hong Kong food because of her Celiac disease often made her feel not good enough.

The more and more she created and the more projects she worked on, Hotung's realized that someone out there was bound to be angry no matter what she did. So, instead of perceiving herself through the eyes of others, she can now focus more on how she feels about her connection to Hong Kong.

"But all these things – of thinking that I'm not good enough to be a Hong Konger because I can't eat the food, I'm not good enough to be a Hong Konger because I can't speak the language – I'm caring less just because I realize sometimes nothing will ever be enough for other people. And if it's enough for me, it's fine," she says.

This all goes back to her early days in art class, expressing herself through art for the love of it rather than to earn accolades and admiration.

"That's where The Hong Konger came from. That's where my art now comes from," she says, "a place where I know I don't have to be the most technically brilliant artist… I just need to make myself happy."

From its down-to-earth themes to references to Chinese idioms, The Hong Konger covers tell of an illustrator who's both observed and understood the intricacies of being from Hong Kong.

And, just by the sheer abundance of art she's done in its name, she clearly has a passion – even a love – for the city, its people and its culture.

We'd say that's enough for us, too.

Comments ()