What we know about the discovery of DNA, 70 years later

It was back in 1953 that scientists revealed that DNA had a very specific shape.

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

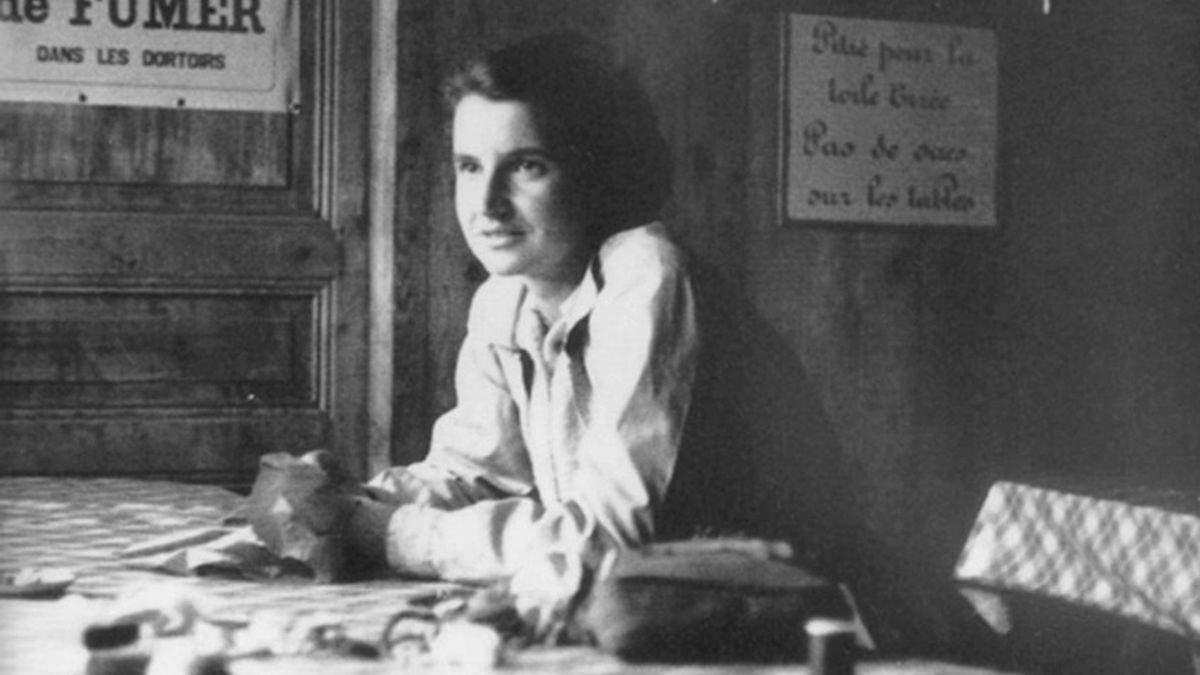

It was back in 1953 that scientists revealed that DNA had a very specific shape, with credit for understanding its structure going to James Watson and Francis Crick at Cambridge University. But it was actually scientist Rosalind Franklin at King’s College London who discovered that DNA came in the double-helix shape that we know and love. Using an X-ray, she and scientist Maurice Wilkins captured an image of DNA’s criss-cross ladder shape, famously known as Photograph 51.

Franklin’s involvement in the discovery of DNA has been minimized throughout history. One version of the story attributes the actual shape-identifying to Watson after he saw Photograph 51, as Franklin hadn’t yet figured it out. It also says Crick got a copy of Franklin’s data and used it without her permission. They both went on to publish a paper in 1953 identifying DNA’s double-helix, which earned them the Nobel Prize around a decade later.

In Crick’s own book, “The Double Helix,” he wrote, “Rosy [Franklin], of course, did not directly give us her data. For that matter, no one at King’s realized they were in our hands.”

But historians and scientists have recently found evidence that Franklin really did contribute to the discovery of DNA in a few major ways. A draft of a Time magazine story at the time suggests that the work the scientists were doing on the DNA structure was collaborative and that Franklin knew the others had access to and were using her own data.

As for Franklin’s individual contributions to the research, she figured out the differences between the A and B forms of DNA, which had confused other researchers. Her measurements also showed how big the DNA unit cell actually is, and she noticed symmetry in the unit cell. Although she didn’t appreciate it at the time, this symmetry discovery was really major in building later DNA models. She was also able to independently learn how DNA specifies different proteins, which Watson and Crick also figured out around the same time.

“We should be thinking of Rosalind Franklin, not as the victim of DNA, but as an equal contributor and collaborator to the structure,” said Dr. Nathaniel Comfort, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Sadly, Franklin died of ovarian cancer at the young age of 37, missing out on any chance at the Nobel Prize. But, looking back at history, we can see that Watson, Crick, Franklin and Wilkins all collaborated in different ways to understand DNA better.

Comments ()