International Criminal Court says offshore detention centers violate international law, but will not prosecute Australian government

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

Responding to evidence from Australian Independent MP Andrew Wilkie, an International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor said that Australia’s offshore detention centers violate international law.

Yet despite finding that conditions in the centers are “cruel, inhuman or degrading”, the ICC will not prosecute the Australian government for human rights abuses.

According to The Guardian, the prosecutor acknowledged that there is evidence that the imprisonment of refugees and asylum seekers amounts to a crime against humanity, but concluded that the ICC will not take the matter further at this time.

What did the letter say?

The ICC prosecutor sent Wilkie a letter in response to allegations he made against the Australian government. The MP for Clark said Australia had committed crimes against humanity against migrants and asylum seekers detained in offshore detention centers. The correspondence, dated February 12, 2020, contained a detailed response to evidence submitted by the MP.

According to Phakiso Mochochoko, the director of the Jurisdiction, Complementary and Cooperation Division of the ICC Office of the Prosecutor who wrote back to Wilkie, the “conditions of detention and treatment … appears to constitute the underlying act of imprisonment or other severe deprivations of physical liberty."

“The gravity of the alleged conduct thus appears to have been such that it was in violation of fundamental rules of international law”, Mochochoko added.

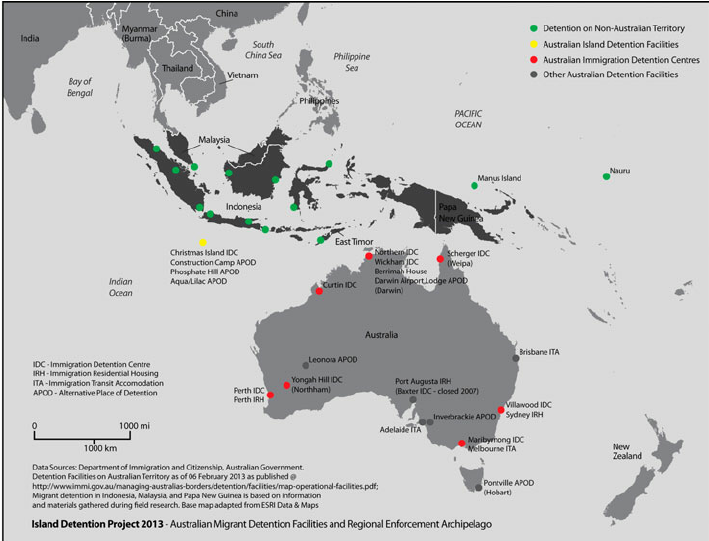

The ICC also found that migrants and asylum seekers kept in detention centers such as the ones on Nauru and Manus Island stay there on average for one year. While in the detention centers, detainees live in “unhygienic, overcrowded tents or other primitive structures”.

Many suffer from illnesses like heat stroke, which the ICC says stems from “a lack of shelter from the sun and stifling heat”. Inadequate healthcare facilities also result in “digestive, musculoskeletal, and skin conditions”, according to Mochochoko.

Alongside the health problems, the ICC details an “environment rife with sporadic acts of physical and sexual violence committed by staff at the facilities and members of the local population" that make conditions in the detention centers worse

Another concern outlined in the letter was the mental impact on migrants.

The “duration and conditions of detention" have caused “measurably severe mental suffering", especially among children. Many of the people kept at the detention centers suffered from anxiety and depression, leading them to try to commit suicide.

The ICC reports there are few provisions for detainees who have mental health issues.

The ICC will not prosecute

Despite the condemnation, the prosecutor said the ICC could not take the matter further because it did not fall within the court’s jurisdiction. Mochochoko said that although the policy was one of “immigration deterrence" there was no evidence to suggest that “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment" was a “purposefully designed aspect" of the program.

The ICC also said that the Australian government doesn’t use the detention centers to “attack" migrants and asylum seekers.

But Human Rights Lawyer Greg Barns argued that Australia had breached international law.

“It is extraordinary and shameful that a nation which purports to believe in the rule of law should be found to be in breach of the international law which outlaws cruelty and inhumanity," Barns stated.

Andrew Wilkie first complained to the ICC five years ago and, according to SBS, has been sending the prosecutor evidence of abusive practices ever since. The MP said their findings were “remarkable condemnation" of the “cruelty" of the asylum seeker policy.

“We’ve long known that the government’s response to asylum seekers has been barbaric, inhumane and expensive," Wilkie said. “But now there can be no doubt that it also puts Australia in breach of the Rome Statute and guilty of crimes against humanity."

Although the ICC found no grounds for prosecution, Wilkie told reporters he would continue his campaign against the detention centers. He said that “recent developments in the government’s asylum seeker policies have opened up new avenues for further investigation and I am currently seeking legal advice as to the next step forward."

Alongside his frequent correspondence with the ICC, the MP for Clark previously introduced legislation that would abolish mandatory detention for asylum seekers, saying, “There needs to be a new conversation about how we, as a civilized nation, respond to people genuinely fleeing for their lives, who have suffered unimaginable atrocities, and now need our help."

Australia’s offshore detention centers

According to Mary Crock, University of Sydney immigration law specialist, Australia’s history of processing asylum seekers offshore goes back to the 1960s. Australia used offshore processing “in a sense, after the Vietnam War” with “the regional processing regime established right across South East Asia”. However, Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating was the first to mandate that “unlawful arrivals" be detained, in 1992.

In 2001, the Howard government introduced the Pacific Solution policy. This legislation saw asylum seekers who arrived by boat be detained and processed in offshore centers on Nauru and Manus Island.

According to The Guardian, there are about 230 refugees and asylum seekers on Nauru and about 180 in Papua New Guinea. These numbers reflect a 23 percent decrease since 2014, according to figures disclosed in Senate Estimates.

As well as the ICC, the United Nations (UN) has criticized Australia’s offshore detention of migrants and asylum seekers. In 2018, the organization condemned the country for holding detainees in indefinite detention. In the same year, the UN demanded that the Australian government close and evacuate the detention centers amid fears of an unfolding health crisis.

In addition to the offshore detention controversy, the government removed income and housing support for housing asylum seekers in Australia. Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur for Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, called the decision “ruthless."

According to the Human Rights Watch 2019 World Report, Australia performs well when it comes to civil and political rights. On the international stage, where it is a current member of the UN Human Rights Council, the country took the lead in condemning Saudi Arabia for violating basic freedoms. But the report says the country has serious human rights issues of its own, mainly relating to asylum seekers and refugees. The report labels offshore detention program “draconian,” highlighting that at least 12 refugees and asylum seekers have died in offshore detention centers since 2013.

The Australian government continues to defend itself in the face of criticism. Government officials have argued that the detention policy “is administrative in nature and not for punitive purposes" and has successfully deterred asylum seekers from Australia.

SBS reports that Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton believes the approach stops people smugglers from targeting vulnerable asylum seekers. Dutton also claims the policy is working because many former detention center detainees end up resettled in other countries.

Comments ()