What is the Insanity Defense?

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

A decision by the United States Supreme Court could allow states to eliminate the so-called “insanity defense” that allows a criminal defendant to argue that they are mentally incapable of understanding right from wrong.

As of now, only five states fail to allow the insanity defense, but it is believed more states may move to bar it.

Though the insanity defense is often referenced in popular culture, its actual use as a legal defense has a spotty record.

Since the 1980s, the burden of proof for an insanity plea has fallen on defense teams, meaning they have to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that their defendant lacked a fully functioning mental state that would otherwise allow them to be held fully culpable.

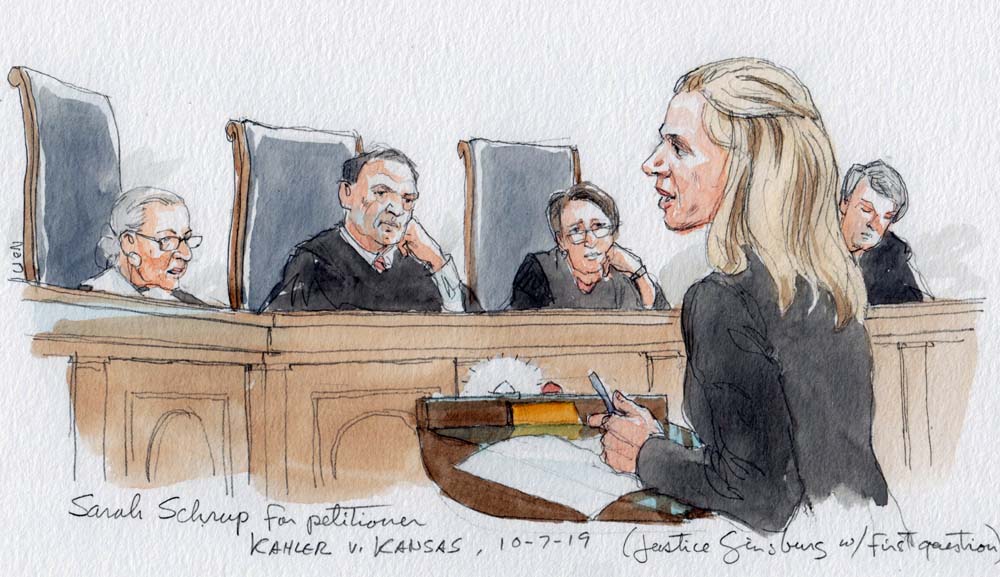

The Supreme Court decision

On Monday, March 23, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in support of upholding a lower court’s decision in Kahler v. Kansas. In its decision, the Supreme Court stated, “Due process does not require Kansas to adopt an insanity test that turns on a defendant’s ability to recognize that his crime was morally wrong.”

The decision was related to James Kahler’s murder of his wife, their two daughters, and his wife’s grandmother. Kahler had claimed mental illness explained his actions, but the jury found him guilty and sentenced him to death. Kahler’s case was appealed up to the Supreme Court.

Kansas is one of only five states that have essentially eliminated the insanity defense. With the Supreme Court upholding the state’s position in this case, though, many other states may soon adopt similar statutes.

Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote the court’s decision, generally sides with the liberal justices of the court, but sided with the five conservative Justices this time. Her explanation for the decision largely rested on the “uncertainties” involved in diagnosing the mind.

“Across both time and place, doctors and scientists have held many competing ideas about mental illness,” Kagan wrote. “Formulating an insanity defense also involves choosing among theories of moral and legal culpability, themselves the subject of recurrent controversy.”

Dissent from the majority decision

The three opposing voices to the majority opinion were Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Breyer wrote the dissenting opinion for the three liberal justices.

Breyer deferred to legal precedent and the assumption that for a crime to be punished, there must be “will and purpose” reliant on “the presence of reason, free will, and moral understanding.” For legal purposes, it has generally been held that a “madman” has no more culpability than a wild animal.

“A defendant who, due to mental illness, lacks sufficient mental capacity to be held morally responsible for his actions cannot be found guilty of a crime,” Breyer added. “This principle remained embedded in the law even as social mores shifted and medical understandings of mental illness evolved.”

What is the insanity defense?

In legal proceedings, a criminal conviction relies on the concept of intention, or “mens rea” (a Latin term meaning “guilty mind”). In a court case, the prosecution must prove both that a person committed a crime and that the actions taken were intentional.

However, a plea of insanity complicates matters. Such a plea allows that the act and intention were there, but alleges that the intention was due to flawed or lacking mental capacity. Going back to the founding of America’s legal system, courts have found that the inability to reason rationally excuses criminal action. A similar argument is used to absolve young children of crimes.

In legal settings, lacking this mental ability is known by another Latin term, “non compos mentis” (“not of sound mind”). If a person is found to be “non compos mentis,” they cannot be held responsible for their actions.

Uses of the insanity defense

One of the most high-profile uses of the insanity defense was related to a mass shooting. On July 20, 2012, during a showing of the Batman film “The Dark Knight Rises,” James Holmes entered a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado armed with multiple guns. He shot and killed 12 people and injured 70 others.

In his trial, Holmes’ defense team attempted to show that Holmes was mentally unfit and thus not responsible for his actions. Ultimately, the jury rejected the claim. Holmes was sentenced to life in prison.

Ben Markus, who reported on the verdict, observed, “A mixture of sadness and relief swept through the families in the courtroom as it was immediately apparent that Holmes’s insanity defense had failed.”

There are notable instances of the insanity defense being successfully used in the US, though.

For example, the would-be assassin of President Theodore Roosevelt, John Schrank, was deemed insane by doctors and sentenced to life in an asylum.

Another attempted presidential assassination led most states to change their laws regarding the insanity defense. John Hinckley Jr. shot (but did not kill) President Ronald Reagan and later claimed he had done so to impress the actress Jodie Foster. The insanity defense worked and Hinckley was acquitted.

In response to the Hinckley verdict, two-thirds of US states changed their laws so the burden of proof for insanity fell on the defense team. Previously, most state laws required the prosecution to show evidence of the defendant’s sanity.

The first successful use of “temporary insanity” (often associated with crimes of passion) as a defense goes back to 1859, when an American congressman, Daniel Sickles, shot and killed his wife’s lover. The victim was Philip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key, who wrote America’s national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

[article_ad]

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters here!

Comments ()