Understanding the legacy of “Trickle-Down Economics”

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

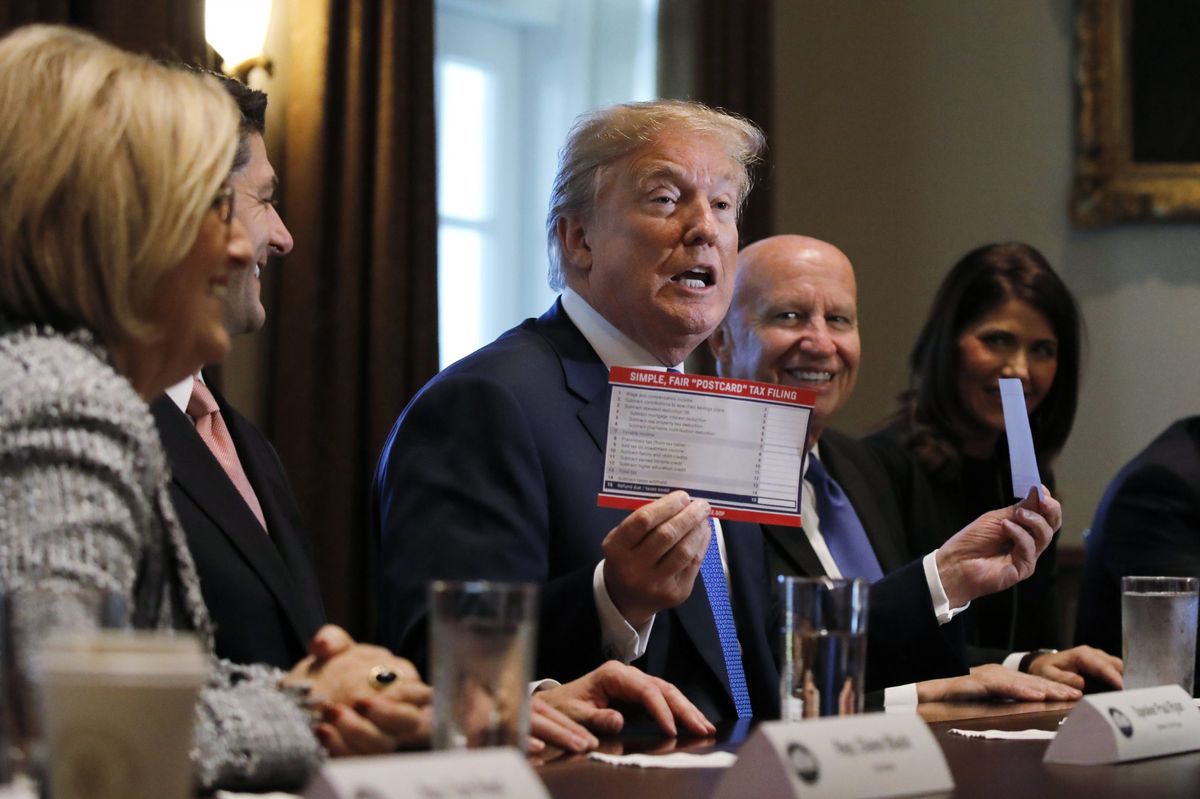

Though originally a criticism of the economic policies of President Ronald Reagan, “trickle-down economics” is now the phrase most commonly associated with the supply-side economic theory that underpinned so-called “Reaganomics.” It has become so ingrained in the culture that even the current Trump administration has used the phrase positively when describing their economic policies.

As a political weapon, “trickle-down economics” failed to curtail the Reagan administration’s economic plans. Since Reagan’s full-throated embrace of supply-side economics, the Republican Party (also known as the GOP) has continued to base their anti-tax, pro-business economic policies on the theory that greater wealth at the top of society will result in greater wealth at the bottom.

Now, nearly 40 years since those policies took effect, the growing wealth divide in the United States suggests that the legacy of trickle-down economics is one of failure.

The Millennial Source spoke with economists to put the theory into historical context.

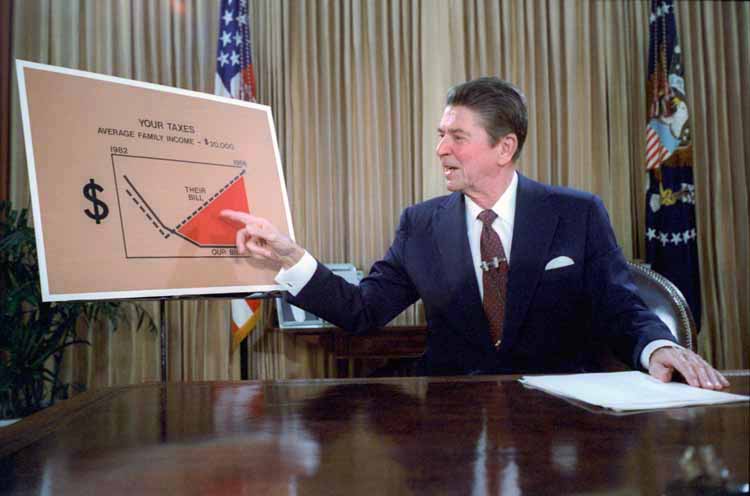

The captain of Reaganomics

An article in the December 1981 issue of The Atlantic offers perhaps the best window in which to view how Reaganomics came into existence. It also provides insight into the mind of David Stockman, a Reagan administration official charged with making supply-side economics work in the federal government.

Writer William Greider conducted multiple interviews over a period of several months with Stockman, before the latter became the director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in the incoming Reagan administration.

Stockman, a US Congressman at the time, was to lead what Greider called a “small but awesomely complicated power center in the federal government.”

Soon to hold “one of the most powerful positions of government,” Stockman was the man charged with making Reagan’s seemingly contradictory campaign promises – lower taxes, higher military spending, a balanced budget – a reality.

Faith in trickle-down economics

The success of the Reagan administration’s theory was reliant on the idea that the private business sector would grow so substantially, it would make up for any loss of revenue caused by reducing income tax. The resulting “robust” private sector would thus reduce government responsibility because private citizens would be better off.

Stockman embraced supply-side economics after being tapped for the OMB director position, but he still acknowledged that “the whole thing is premised on faith.” It assumed that investors and businesses would see the government’s actions as a positive indicator and would increase investment.

As Greider explained, supply-side economics was a new name for the Republican Party’s economic theory – a theory that had existed for generations.

“Give the tax cuts to the top brackets, the wealthiest individuals and largest enterprises, and let the good effects ‘trickle down’ through the economy to reach everyone else.” Stockman conceded, “Supply-side is ‘trickle-down’ theory.”

(An amended note on the story from 2019, following Greider’s death, reports that Stockman was harshly rebuked by Reagan for speaking “too freely” about his doubts of the administration’s policies.)

The notion of money trickling down to the poorer classes from the rich was a concept satirized by American humorist Will Rogers during the Great Depression. Rogers said that the administration of President Herbert Hoover assumed that money would “trickle down to the needy,” but that, in fact, “money trickled up.”

The legacy of trickle-down economics

Speaking with The Millennial Source, Dr. Michael Merrill, Professor of Professional Practice and the LEARN Director for Rutgers University, explained that so-called trickle-down economic theories aren’t inherently flawed, but they are ill-suited for the United States.

“[In the US] the most profitable investments are often passive financial speculations. The gap between investment and employment is so wide that the former does not always translate into the latter. The rich can make money whether the poor are working or not. And they do. As a result, giving money to rich people doesn’t ‘trickle down’ as much as it once did because the rich have lots of ways to make money with less risk than investing in competitive enterprises.”

Republicans may distance themselves from Reaganomics because of the negative association of the “trickle down” label, but, Merrill explains, their policies – “Starve the public sector and feed the private sector” – remain largely unchanged.

Merrill defines the prevailing Republican economic theory as follows.

“The worst thing you can do is anything that benefits the poor directly. According [to] the Republican orthodoxy, the poor don’t know what to do with any advantage you give them. If they knew how to manage money, they wouldn’t be poor.”

If the GOP’s policy has changed since Reagan, Merrill doesn’t believe it’s for the better.

“Republicans no longer worry about borrowing huge sums of money and running up large deficits, so long as the money goes to them and their friends.”

Lest it seem as though Merrill is making a partisan argument, he also criticizes the opposition.

“The dominant Democratic economic theory is indistinguishable from the dominant Republican theory, as far as I can tell. The Democrats are a little more willing to give money to people who need it rather than just to the people who already have it. But not that much more generous.”

An alternative in the US

Merrill, who says he “came of political age in 1968 in the civil rights and anti-war movements” has spent decades teaching about the “political economy to union members and community activists.” He advocates for democratic socialist policies, such as those common in European countries that have stronger social safety nets than the US.

Those policies were supported by Senator Bernie Sanders, the progressive candidate who dropped out of the presidential race earlier this year. Sanders has long advocated for expanding government spending in multiple sectors, including healthcare and education.

Yet Merrill questions if Sanders’ policies address US economic issues sufficiently.

“[Sanders] doesn’t talk nearly enough about public investment and employment assurance programs for my taste (i.e., policies that provide jobs for all who want to work, though the jobs will change as circumstances change). Until we take employment out of competition, eliminate job blackmail and wage extortion, we will remain stuck with our current Sheriff of Nottingham economy, which takes from the poor to give to the rich rather than the other way round.”

Though Merrill expresses dismay with the “current political leadership” in the US, he says he is heartened by younger leaders who are embracing democratic socialist policies. He emphasizes that such policies are about an equal partnership between the government and the private sector.

“The only way forward is to strike a dynamic balance between a strong, thriving private sector and a strong, thriving public sector. Each will help to keep the other honest.”

The US’s economic disparity

Dr. Tenpao Lee, a professor of economics at Niagara University, tells The Millennial Source that the GOP’s economic theories have helped worsen the wealth gap between the rich and the poor in the US.

“In terms of the equity income distribution, the USA was the worst among developed countries,” Lee explains. “The Gini coefficient to reflect income distribution was 47% (USA), 38% (Japan), 32% (UK), and 27% (Germany), respectively. The higher the Gini ratio, the higher the gap between the rich and the poor.”

Lee fears that the current COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting recession will only worsen that gap.

“Specifically, 10% of the rich owned 81% of the stock market and the GOP economic theory is virtually in favor of the rich, such as lower taxes, free market capitalism, deregulation of corporations, and restrictions on labor unions.

“In addition, small businesses with less access to the capital market are hurting the most during the Pandemic. Some of them will disappear permanently and some of them will no longer be profitable in the reopening economy as their capacity has to be cut in half or less (e.g. small restaurants, barber shops, small stores).”

Dr. Merrill agrees that the pandemic is heightening the country’s economic disparity.

“The coronavirus epidemic has made the crisis acute. It is a wake-up call. It remains to be seen whether we will wake up and answer the call. I am hopeful but not particularly optimistic. I do think that as long as the epidemic is with us, people will keep dying and others will keep protesting. What have we to lose?”

Do supply-side policies ever work?

Merrill makes it clear that he doesn’t believe supply-side economics is an untenable theory. On the contrary, he argues, it can be very successful in poorer countries. It can even work in rich countries if there are methods of ensuring that the money isn’t “siphoned off by brokers and others before it reaches the people who need it.”

“Obviously, corruption is a problem [in] poor countries,” Merrill concedes. But, he argues, the benefits of investing in businesses in poor countries still outweigh the risks.

“That’s one of the reasons private sector investment is beneficial in poor countries. The investors have an incentive to watch the store! It is a counterweight to public corruption. But in rich countries, the private sector has lots of ways to enrich itself without doing anything. Economists call it ‘rent-seeking’.”

In such countries, “the most profitable investments are often in more labor-intensive, goods-producing and service-providing industries that provide jobs and income to large numbers of people.”

According to Merrill, the US isn’t the type of environment that needs supply-side policies.

“We are rich enough to be able to afford sharing our prosperity with others. If we don’t, we can expect continuing pain and protest, among other catastrophes.”

Merrill also disagrees with the idea that the poor can’t be trusted to manage their money.

“We need a rise-up or bubble-up economics that gives money to working people. They will spend it in the right places (after all they have none to waste), putting other people to work doing useful things.”

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()