15 Years after Katrina: Understanding the storm’s lasting impact on New Orleans

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

For many residents of New Orleans, Louisiana, August 29, 2005, marked a turning point, not just in their lives but in the character of their city. A decade and a half later, Hurricane Katrina’s cataclysmic impact on NOLA has been retold in films, books, television series and music. Images from the storm’s destruction have become an indelible part of the history of New Orleans and the surrounding region.

But Katrina wasn’t the end of the story for one of the United States’ oldest cities. 15 years after Katrina swept through the Gulf of Mexico, much of the city has been rebuilt and strengthened. Founded in 1718, New Orleans’s devoted residents hope to see their unique city thrive for another 300 years.

Over the past month, TMS has spoken with multiple residents of NOLA who experienced the immediate impact of Katrina firsthand and are living there now. They shared how the city has changed since the hurricane – in ways both good and bad – and whether the city is prepared for another powerful storm.

We also heard from Zack Rosenburg, a co-founder of SBP, whose mission is to rebuild New Orleans and prepare the community for the challenges of the 21st century.

These stories aim to provide a fuller picture of New Orleans 15 years after this tragedy.

Out of the path of Hurricane Katrina

Gloria DeCuir, an adjunct instructor at Delgado Community College, has lived in New Orleans for 65 years. She was among the 80% of citizens fortunate enough to evacuate prior to the storm. DeCuir returned in the fall but didn’t settle back into the city until spring 2006.

She never contemplated not returning to her lifelong home, though she and her husband did consider purchasing a second home in Humble, Texas.

“We lost a car, truck, furniture, clothing, appliances, miscellaneous home items, tools, a computer, [a] violin and electronics,” DeCuir says. “Fortunately, most of our furniture was in storage on the Westbank (no water damage). We had eight feet of water in our raised home at the London Avenue Canal.”

Dee Boling, the Senior Director of Marketing and Communications at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, also lost a great deal in the flooding that followed the storm.

“The water was 10-ft high on our street, which meant that we got seven feet of water in our house,” Boling says. “Since it’s a single-story house, that meant the entire house was flooded, floor to ceiling. Very little was salvageable. Thankfully we evacuated with about half of our photos and our family Christmas decorations were in the attic.”

Like DeCuir, Boling evacuated before the storm’s arrival, going to her mother-in-law’s house in Stone Mountain, Georgia on August 27.

“My husband returned in early October. I made a visit in October, but didn’t return with my toddler until January 2006.”

Rebuilding New Orleans

While DeCuir and Boling were both long-term residents of New Orleans prior to the storm, Zack Rosenberg was living in Washington, DC when Hurricane Katrina hit.

Rosenburg and his business partner (now wife), Liz McCartney, were lawyers who came to Louisiana six months after the storm struck to help rebuild, only to find little work being done. Their intention was for it to be a two-week volunteer trip, but it ultimately became much more.

“We joined up with an organization feeding 1,200 people each day in St. Bernard Parish, one of the communities hit hardest by Katrina,” Rosenberg says. “We slept in tents in the back of an Off-Track Betting building, cooked food, and spent time with the residents who reminded us of our family. We got to know these people, and after two weeks couldn’t leave them in their suffering.”

Together, Rosenburg and McCartney quit their jobs in Washington and permanently relocated to New Orleans. They launched the St. Bernard Project, a nonprofit recovery relief program now known as SBP. SBP “serves low- to moderate-income residents with a special focus on families with small children, the elderly, disabled persons, war veterans and the under- and uninsured.”

SBP has now rebuilt nearly 800 houses throughout NOLA while providing rentals to low-income families and opening up opportunities for first-time homeowners.

“We feel a moral imperative to support disaster-impacted communities and the most vulnerable populations whose voices often aren’t heard,” Rosenburg told TMS. “We must amplify their voices and advocate for the right to safe and secure housing.”

The Superdome and the Super Bowl

I lived in New Orleans for a year, from 2012 to 2013, arriving in the city on September 1, 2012, four days after Hurricane Isaac. That Category 1 storm briefly passed over New Orleans, almost seven years to the day after the city was hit by Katrina – a Category 5 storm. Other than the French Quarter, most of the city was without electricity for half a week or longer.

My first few days in the city were spent sweating through intense heat and humidity. The city’s water supply was also temporarily put under a boil advisory, meaning tap water needed to be boiled before it could be consumed. Arriving in the wake of a hurricane was a harsh introduction to the city, even though Isaac had been far less destructive than Katrina.

Within a month of moving to the city, I took a job at a restaurant in the Central Business District. One of my co-workers there was Chris Woods, currently an English teacher at Jesuit High School in Mid-City, the same school he attended as a teenager.

Woods and I worked together the night of Super Bowl XLVII, which was being held at the recently renamed Mercedes-Benz Superdome less than a mile away. It was an eventful Super Bowl: the Baltimore Ravens beat the San Francisco 49ers 34-31, Beyoncé headlined an extravagant halftime show and, dramatically, the stadium’s power went out for 34 minutes in the 3rd quarter.

With the eyes of the world on the city for the biggest sporting event of the year, the power outage was a reminder that New Orleans remained a work-in-progress seven and a half years after Katrina.

The Superdome infamously played an important role during Katrina, housing nearly 16,000 people throughout the storm’s barrage and in the days after the hurricane struck. It provided lifesaving shelter, but after it lost electricity, the stadium also became a sweltering cage for many locals who didn’t or couldn’t evacuate.

Repairs to the Superdome cost US$366 million, a substantial sum, though relatively minor compared to the multibillion-dollar price tags of new stadiums in the National Football League.

In the lead up to Super Bowl XLVII, which occurred in the middle of that year’s Mardi Gras festivities, the city raced to prepare for the surge of football revelers and national attention it was sure to receive. Besides beautifying parts of the city that would see increased tourism, the city council invested considerable effort in repairing sidewalks.

The neighborhood I briefly lived in, St. Roch, noticeably transformed during my year in New Orleans. At the end of my former street sat a historic food market that was nearly destroyed during Katrina. By the time I moved away, the dilapidated building had gotten a face-lift, though finishing the project would take a few months more. The St. Roch Market reopened in 2015.

The gentrification of New Orleans

Woods, who was born and raised in New Orleans, has watched the city change considerably in the last 15 years. Though he says his family was lucky – “we only lost things in storage on the first floor of our home” – the storm did take one important thing away from him: “My senior year.”

His family left New Orleans on the morning of August 29, not the first time he had evacuated the city.

“I had evacuated so many times, I treated it like a mini-vacation, and only packed a single change of clothes. Because I was a senior in high school at the time, I did not return until December.”

So, all these years after the storm, what changes does Woods see in his hometown?

“The biggest change is probably the gentrification/outside investment in the city,” Woods says. “Lots of property in ‘desirable’ areas became available because people either didn’t want to come back or couldn’t afford to. This led to a lot of different investors, many from outside the city/state, to come in and buy up property. They turned a lot of these places into Airbnbs, which increased the prices of apartments as there were a lot fewer places available.”

Gentrification has pushed many poor and African American residents out of the city, he laments.

In 2019, Bloomberg reported on a study that found that the neighborhoods damaged the most by Katrina experienced the most gentrification. In addition to pushing poorer residents out of those neighborhoods, this gentrification led to a greater concentration of African American residents settling in other neighborhoods, increasing “racially-concentrated poverty.”

DeCuir also called gentrification one of the biggest changes she’s witnessed in New Orleans since Katrina. She fears it is watering down the city’s rich culture and the unique neighborhood practices.

She lists the many ways New Orleans has changed for the worst post-Katrina.

“Loss of jobs and homes. Low pay wages. Lack of affordable housing due to low wages. High rental costs; especially for essential workers.”

She also fears the city’s music culture – the heart of New Orleans – is being lost.

The changing face of New Orleans

It was perhaps inevitable for a city that experienced so much devastation to lose some of its character, especially with out-of-state investors moving in to take advantage of cheap real estate and business opportunities. Not all the changes have been bad, though.

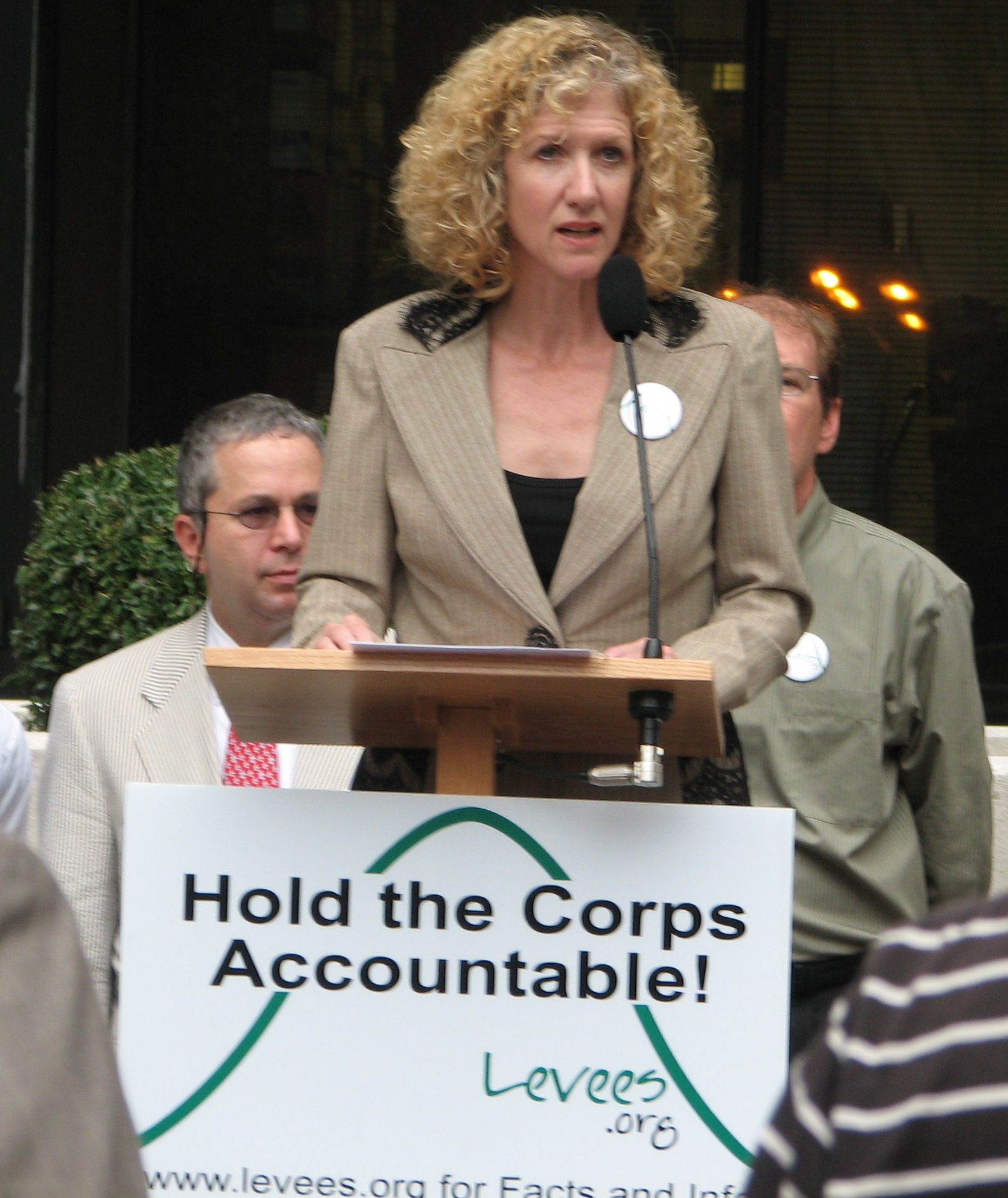

Sandy Rosenthal has been a resident of New Orleans since 1980. She lives with her NOLA-native husband of 41 years and is the author of “Words Whispered in Water: Why the Levees Broke in Hurricane Katrina,” out this month from Mango Publishing.

Rosenthal’s family evacuated the day prior to the storm and didn’t return until December 14. Her son, like Woods, was still in school and did not have class again until January 2006. She said her family’s home was fortunate to be situated above the flooding, though her husband’s business “sustained an inch of water which caused mold.”

While recognizing “the pain and the trauma” that so many residents still live with, Rosenthal says there have been a few bright spots for the city since the storm.

“The public schools, in every measure, are better than prior to the levee breach event,” Rosenthal states. “In addition, there’s a ‘can do’ attitude. We have raised our property taxes and sales taxes and become a more responsible city.”

“I think the biggest change is the almost aggressive determination to move on,” is how Boling puts it. “We had restaurants and festivals before Katrina, but now we have more than double the number of restaurants and many more festivals than before celebrating everything from daiquiris to fried chicken to macaroni and cheese. Culture has become something not only to hang on to but to capitalize on.”

Rosenburg and SBP want to be part of that positive change, specifically by focusing on infrastructure and communities. He sees it as the role of nonprofits like his own organization to work alongside communities to tackle social inequality in New Orleans and other similarly ravaged places, especially as “natural disasters increase in frequency and intensity, largely due to human-fueled climate change.”

“One pathway to building resilience and social equity is through increasing the stock of affordable housing. [SBP] recently began expanding our work in that direction through an Opportunity Housing program that creates homeownership and rental opportunities for residents of low- to moderate-income while rehabilitating blighted properties and strengthening neighborhoods.”

Where is New Orleans’ recovery now?

The general consensus of those interviewed for this story was that New Orleans had not fully recovered from Hurricane Katrina, though there was reason for optimism.

“It is my hope,” SBP’s Rosenburg says, “that we put ourselves out of a job; that we not only recover, but prepare to the extent that a disaster recovery non-profit is no longer needed.”

DeCuir states, “The city is on its way to fully recover, but it has and will come at a cost.” The influx of money from outside the city has spurred that recovery, but it has also meant some of the city’s most storied neighborhoods – Treme, Gentilly, Mid-City – historically home to artists and musicians, now lack affordable housing.

Rosenthal offers an even bleaker response.

“No the city has not fully recovered. A short drive in a car demonstrates that. Huge swathes of land, which once supported homes and playgrounds still lay bare and overgrown with weeds.”

To her, the loss of the city’s population is the most notable change since Katrina.

If the city hasn’t recovered, maybe some of its people have. Or, at least, moved on.

“I don’t really think about Katrina anymore,” Woods admits.

Boling is more circumspect in her answer.

“‘Recovered’ is an interesting term. You can recover from breaking a leg, but still have signs of the break show up on an X-ray or know when a big rain front is coming because it aches. I think recovered is even more complicated since there were plenty of things that didn’t work well or efficiently before Katrina.

“We are a fully functional city with a lot going on but you’ll always be able to see the fault lines of Katrina. We’re also never going to be as efficient as some other cities because we allow imperfection here in ways other cities pave or paint over.”

The future of New Orleans

Asked if New Orleans could survive another Katrina-level hurricane, these NOLA residents were hopeful, but cautiously so.

“I think, yes, it could withstand a Katrina-level hurricane,” Woods answers. “However, what comes after is the bigger issue. Recently, we have gotten through tropical storms and hurricanes with ease. A few weeks after, though, a set of strong storms will come through and flood the city out of nowhere.”

The issue? New Orleans’ infrastructure.

“The city’s pumps are over 100 years old, and when they are working at full speed, they tend to break. In summer months, we get afternoon showers almost daily that will dump a few inches of water in just a couple of hours. The city pumps or generators will break, and neighborhoods will flood. It is so unpredictable.”

Rosenthal’s assessment is a bit more optimistic, but still acknowledges room for improvement.

“After the Army Corps of Engineers’ levees breached in fifty places, Congress gave the agency US$14 billion and told them to do it right this time and do it really fast. Yes, the city is much better prepared to survive a Katrina level hurricane, mainly due to the Billion Dollar Surge Barrier just east of the city and also because the agency has built gates at the mouths of the city’s three largest drainage canals.

“My biggest concern is that for just a couple of feet of levee height, the corps could have improved flood protection by a factor of five in the city’s main basin which has the most people, property and infrastructure. But the decision by the Bush administration in 2005 was a political one, not an economic one.”

DeCuir is far gloomier – and more succinct – in her assessment of whether NOLA is prepared: “No.” She, however, does believe that if another Katrina-sized storm did come, people would be better prepared and would leave sooner.

“There is still much work to be done,” Rosenburg says, “but that work looks different today than it did five, even ten years after Katrina. Now we are working to build stronger, more resilient communities, ones that can withstand any kind of disaster from flooding to a global pandemic. Whereas recovery can be marked by the number of families who have returned home, resiliency is ongoing and must continue to be a factor in how we build moving forward.”

Whether the city is prepared or not, for Boling, New Orleans must survive, because there is nothing else like it in the country.

“New Orleans is the most unique city in America,” Boling explains. “We have terrible health and wealth inequity, but we also have a very vibrant, organic culture that crosses racial and economic barriers. There’s nothing manufactured about the ways people interact here socially. Everyone talks to everybody else, and that was the thing I missed most when we were evacuated.

“New Orleans matters. It was worth saving after Katrina and it’s worth protecting it now. You could never recreate New Orleans someplace else.”

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()