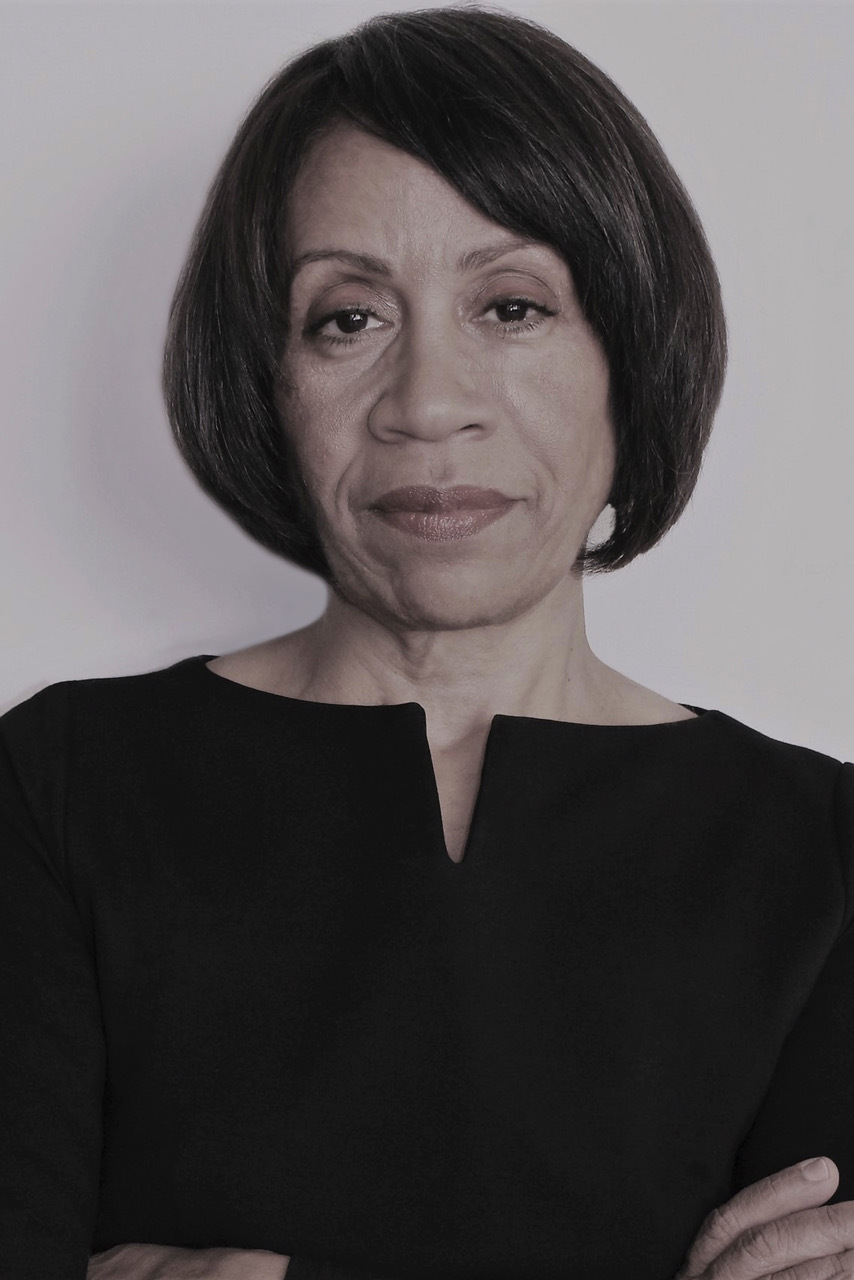

“Anybody can be a human trafficker.” Taina Bien-Aimé, Executive Director of CATW, on sexual exploitation, QAnon and the dangers of conspiracy theories

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

Human trafficking has gained greater attention in recent years due in part to the arrests of Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. Yet, the issue has also become fodder for one of the most insidious conspiracy theories in recent memory, QAnon, which claims a Satanic cabal of powerful figures and celebrities – among them, Tom Hanks and Oprah – are trafficking and raping children.

As the QAnon movement gains a footing in the political world, with more than a dozen Congressional candidates voicing support for it, it can no longer be dismissed as a joke or a right-wing cult. Those who have dedicated their lives to the work of ending human trafficking see considerable dangers in the movement.

TMS spoke with Taina Bien-Aimé, who in 2014 became the Executive Director of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW). CATW has been working to end sex trafficking and sexual exploitation for three decades, through a mixture of advocating for public policy, raising awareness of the issue and supporting survivors.

The organization is headquartered in New York City but works out of offices around the world as it seeks to “create a world where no woman or girl is bought or sold.”

In a wide-ranging phone interview, Bien-Aimé talks with TMS on topics related to her work, from QAnon and the impact of conspiracy theories on the cause, to the way sexual exploitation and its ripple effects are often misunderstood by society.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity. If an answer requires clarification or correction, an “Editor’s note” has been added to provide greater context.

What have you heard about QAnon, how familiar are you with this movement?

As familiar as any reader of mainstream media, The [New York] Times, The [Washington] Post, what is covered on television, Pizzagate, the conspiracy theories. You know, not in-depth. I’ve never followed them. I’ve never researched them thoroughly, but, I would just say, [an] average newspaper reader’s knowledge.

So, you have heard of Pizzagate? You are familiar with it?

Yes, yes of course.

As anti-trafficking organizations, we understand how trafficking works, we understand how insidious it is, how many myths there are around trafficking, how difficult it is to identify victims of trafficking, how elements of corruption are involved in trafficking rings and all that. The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women doesn’t only focus on children, we also, by its name, focus on women. The majority of the news articles are focused on child sex trafficking. Which, you know, the majority of people who were sex trafficked were trafficked as children, so that would make sense but we don’t believe that there’s any difference between a 17-year-old and an 18-year-old when it comes to a sex trafficking victim.

Unless somebody is in some refrigerator truck and bound to radiators, [people] don’t see it as important when it comes to adult human trafficking. And that’s unfortunate and that is something that we address.

Our perspective mainly is to engage in legal advocacy, meaning that where there are laws against trafficking (some are better than others), as an international organization, we follow the principles of the Palermo Protocol which gives us the internationally recognized definition of trafficking. And, so, when you look at all these elements, our focus is mostly, who are the actors and what are the elements that contribute to trafficking. It’s very important to focus on the victim but we’re talking about a market. It’s a global multibillion-dollar sex trade whose every single dollar comes from sex buyers, but nobody really talks about that. You have this market through which buyers … have a taste for bodies, human bodies. Mostly women and girls, but you also have men, boys, transwomen and trans youth, but … an overwhelming number of people who are sex trafficked are women and girls.

The challenges for us, whether you’re looking at conspiracy theories or the issue in real terms is that nobody really wants to address the idea of the market. As was mentioned by a few of my colleagues who were quoted in the paper, on the one hand it is important to raise awareness about trafficking but what can be dangerous is … Well, certainly conspiracies theories are extremely dangerous to our work, but also what’s dangerous is the narrative around it that really distorts people’s understanding of human trafficking and how to address it. That’s usually problematic.

I guess the underlying focus on these conspiracy theories is twofold: we have the political element, clearly, because [in the view of QAnon] there’s one political party that is cannibalistic and totally corrupt and engaged in criminal activities. But the other part is this whole concept of rescuing, which is obviously very important and many anti-trafficking organizations focus on rescuing.

Around the Pizzagate scandal, right, you have this renegade guy who goes to quote-unquote “rescue the kids in the basement.”

[Editor’s note: In December 2016, a follower of Pizzagate, Edgar Welch, entered the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria in Washington, DC, believing it was a child trafficking front and shot three times with an AR-15. After realizing there was no sex trafficking ring in the pizzeria, Welch surrendered to the police. He received four years in prison.]

But you know rescue and restitution is only a tiny part of the human trafficking phenomenon. You know, it’s sort of the symptomatic part, it doesn’t go to the essence of what is human trafficking and how can governments address it.

With the markets that exist, do you think that is something that can only be addressed at a government level, in a criminal sense?

Well, when we have laws in place, it’s the government’s responsibility to enforce them, right, so in that sense, yes, governments are key. They are the ones who enact the laws and they’re the ones who pledge to implement the laws to the fullest extent of their power and political will. That’s one element.

Awareness-raising is also key. Because the majority of people who are trafficked around the world are trafficked for purposes of sexual exploitation and the majority of those people are women and girls, we focus on sex trafficking and how the sex trade operates. We’re talking about simple economics. These are the elements of Economics 101, right? You have supply and demand and the incentive for profit. The sex trade isn’t any different.

There’s a lot of focus generally on the supply: whether or not she’s 18, whether or not she was trafficked, whether or not she consented to it, whether or not she enjoys it. We’re talking about adults who are in the sex trade, but there is very little awareness and very little political will on the part of governments to focus on the demand side. Even with these conspiracy theories, they build up, like, who are the perpetrators and who are the ones who are the actual traffickers. It’s a lot of noise is what it is. It’s a lot of noise that really takes away from the central nerve of trafficking and what it takes to keep these global illegitimate networks from growing.

When you read a conspiracy theory that says something like, Tom Hanks or Oprah is part of this, what is your reaction to that?

I think it’s harmful. I think it’s distracting. I think it diminishes the work of bona fide human trafficking organizations. I think it underestimates the complexities that law enforcement or the US government faces in addressing trafficking, but I would say it’s mostly distracting. And, of course, ridiculous, it’s absolutely ridiculous.

But you also have to see it within a broader political context. Conspiracy theories have always existed, as you know. Our lives have changed. I’ve been doing this for decades and when we started there was no internet, so any theories of conspiracy or any cases of trafficking were [through] paper or calls that informed you of what was happening. And now with the internet and social media in particular, it just expands this storytelling and this really nefarious political storytelling.

Unfortunately, [conspiracy theories are] very effective and I think that’s also what is very dangerous. I mean it’s astounding to see how many followers QAnon has and even if you are not part of either the Tea Party or you know any of those extreme-right groups or people who support the current president, you know, it still seeps into people’s imagination and it distorts peoples understanding of a very serious issue and politicizing it in a way that is not helpful to anyone, especially to the victims.

The QAnon movement is, as you said, very politicized. It very much sees Trump as a leader, as a rescuer. Are you familiar with – I use the term in quotation marks – a documentary out called “Out of Shadows”? I don’t know if you’ve come across that?

[Editor’s note: “Out of Shadows” is a film by a former Hollywood stuntman, Mike Smith, in which he claims powerful Hollywood figures, working alongside the CIA, have been running a Satanic cabal of child rapists and cannibals. While the film never mentions QAnon, the Pizzagate conspiracy theory, which is a precursor to QAnon, is discussed at length.]

I’ve heard of it, but I have no interest in watching it. You know, Satanist cults are as old as the Bible, so that’s nothing new, there’s nothing original or creative about that. We’re talking about the amplifiers and so the question now is what are the platforms going to do about it. I think the Twitters and the Facebooks of the world are trying to address it. They’re not addressing it effectively, but I think that’s sort of the exponential impact of these conspiracy theories. How they arise in this discourse is you just put a hashtag and 300,000 new followers later, it becomes a very popular theory.

“Out of Shadows” doesn’t purport to be QAnon, it doesn’t mention QAnon, but it traffics in very much the same language, the same imagery. I’ve seen parts of that movie shared by very liberal or left-leaning people. Maybe not the entire thing, they’re not sharing the Satanic part but they’re sharing the part about celebrities being part of this trafficking and sharing it through, in particular, #SaveTheChildren or #SaveOurChildren, those hashtags. And it’s now crossing political lines. Whereas QAnon, you basically just associate with Trump, this is starting to become something that’s not really politically aligned anymore as it grows with the hashtags.

Right, because of the targets. If you’re going to reach out to soccer moms or to other affinity groups that are not necessarily political but who have seen enough television or watched enough movies about trafficking to show some interest in it and [they think], “Yeah, we know it’s a conspiracy theory, but maybe there’s a grain of truth to it.” Again, I think that it’s up to these social media platforms to take more responsibility in monitoring and stopping these really hurtful conspiracies from occurring.

I have to go back to the Jeffrey Epstein case. With the Jeffrey Epstein case, it’s not helpful obviously [with] the conspiracy theory because it kind of feeds into the unfounded accusations or sort of the hyperbole. But, I think, that when you see who is involved directly or indirectly with the whole Epstein situations – I mean we’re talking about two presidents, a member of the UK Royal Family, the elite in academia, on Wall Street – the average person understands that it makes the work a lot harder. And what we try to combat and raise awareness about is the level of impunity. Which is not unusual. I mean it’s not just trafficking. I think you see that in other movements that advocates are trying to fight against. Just the lack of political will to address certain human rights violations or even environmental disasters, or people who contribute to environmental crises.

Or, you see it now in the Black Lives Matter movement. It is about how to end the impunity, right, how to bring justice, how to bring attention to protecting vulnerable people and to end systems of exploitation and brutality and violence and that’s a much harder question to address than to just develop a hashtag and count your supporters and followers. You have to say, “To what end? To what end are you doing this?”

We are now in a very polarized political environment. People who hate the other side will hate the other side. It just brings people more fodder to hate the other side … but it distracts from the actual horrors that are happening.

Do you personally, or your organization, have a tangible example of maybe QAnon or its adherents interrupting or getting involved in your work, causing an issue with your work?

No, you know, we’re a small organization. Because our focus is not solely children, I think we were spared. Although, the Polaris Project also deals with all forms of human trafficking in adults and children and they were affected because of their trafficking hotline. The hotline was flooded … and when we have limited resources, obviously if your calls go from 100 to 1,000 within a few weeks, it’s very demanding resource-wise. But, no, thankfully we’ve been spared (knock on wood) to date.

Obviously there is a lot of passion out there for this issue. There are a lot of well-meaning people who want to help. What would you say is a tangible thing a regular person in their daily lives can do to help either your organization specifically or the cause in general?

That’s a complicated question. With these calls for criminal justice reform, which is obviously critically important, with all the hashtags – speaking of hashtags – #DefundthePolice, prison abolition and all that, what we are seeing is also this push among many social justice leaders to call for the decriminalization of the sex trade. What they say is, let’s decriminalize marijuana and let’s decriminalize what they call quote-unquote “sex work.” But it really is decriminalizing the entire sex trade, including pimps, brothel owners, every commercial sex establishment under the sun, sex buyers, etcetera. And that is a very vibrant movement that is causing enormous harm to trying to combat sex trafficking.

People will say, “Well, it’s two different things, you have prostitution on one end and you have sex trafficking on the other.” But the sex trade is where sex trafficking happens and that’s not something that Pizzagate or other conspiracy theories talk about. These things are linked. Again, you have to look at the market and then see sex trafficking is just a vehicle. You have to think of it as a train from which a trafficker or perpetrator brings their victims to an end destination.

In labor trafficking, that end destination is agricultural farms or nail salons or factories, etcetera. In sex trafficking, that end destination is the sex trade … from procuring girls [for] famous people in their yacht or private island, to brothels and escort services, etcetera. So, for us, that is a very dangerous movement. We’re seeing a lot of politicians who identify as progressive politicians who are promoting these policies that are the most regressive possible.

For us, that’s something that people are not really focused on because it is very complex and when we talk about awareness-raising it’s a lot easier to develop a hashtag and, I think, just general psychology could inform you, if you do talk about something that is familiar to people it resonates a lot more. So, of course, if you’re going to talk about the Clintons or Hollywood stars, people are going to pay far more attention than listening to survivors’ voices tell people about how it’s important to hold the people who harmed them accountable to the torture and the harm that they caused. So those are both policy challenges but they’re also awareness-raising challenges. They’re messaging challenges. We live in a culture that is both titillated by what they would call sex, but we’re not talking about sex here, we’re talking about serious sexual exploitation.

My specialty has been in looking at harmful cultural practices that are human rights violations that affect mostly women and girls, so female genital mutilation, girl marriage, polygamy, the list goes on. The sex trade is our harmful cultural practice.

It’s interesting to see this dichotomy in the narratives when you have, on the one hand, this Pizzagate-type thing where you have these absolutely crazy theories of cannibalism and famous people trafficking children, but then, on the other hand, to have this glorification of the sex trade, from “Pretty Woman” and now you have “P-Valley” on Starz and “The Girlfriend Experience.” For advocates like ourselves, it’s very challenging … It’s like two parallel courses that don’t meet each other.

You talked about how it’s easy to talk about the Clintons or celebrities as the people doing these things, but that the sex trade is bigger than that. It’s something that we’re kind of all involved in in some ways. So maybe we should think about it in the way we talk about white privilege or even racism. It’s easy to say someone in the KKK is racist, someone wearing a Nazi emblem is racist, but maybe racism is in all of us. There’s systemic racism and we have to understand that we’re part of it. Would you say that’s true for this issue, that instead of it just being like, “Those people over there are bad,” that we think we all have some complicity in the system?

Systems of racism and other historical systems of oppression and the lack of justice and the lack of access to justice very much is linked to the sex trade. The whole concept of prostitution per se is a concept that was quote-unquote imported by the colonials. You can talk to any Indigenous person, whether they’re the First Nations in Canada, or the Indigenous people here, or Zulus in South Africa, the concept of prostitution didn’t exist. They don’t even have a word for it.

So, when we look at the sex trade, what is it? It’s just simply the buying and selling of human beings for profit that is an enormous incentive for profit. So, you cannot talk about the sex exchange in the US without talking about 1492 or 1619, it’s impossible.

[Editor’s note: In 2019, The New York Times began an ongoing project entitled “1619” that sought to “reframe American history” around slavery’s role in the nation’s development.]

It’s like Sisyphus trying to get people to make the links between what is happening in the sex trade. Who is the population that is being bought and sold? It is primarily – and again this is in the US, but this is across the board – it is the most marginalized, right? It’s homeless youth, of course. Girls. [Those in] foster care systems, kids with histories of sexual violence, homelessness. LGBT youth, especially trans youth, who become homeless or rejected by every aspect of our systems, who then become extremely vulnerable to exploitation. But then again, you have the market for it, so without the demand for those bodies there would be no sex trade.

But our country was built on that framework and especially when it comes to Black women. A Black woman had particular value on the auction block because she could be sold over and over, because she could reproduce other enslaved people, other property. And so it is a question of property when you exchange money for the sexual act, you own that person for that time. The person is the object of your sexual fantasy, that person doesn’t exist anymore. We as a culture see it as consent because money was exchanged.

On the one hand, you have this awareness-raising around the #MeToo movement, around the harms of sexual harassment, sexual violence, dehumanization, how one perpetrator affects the life of one victim for her life or his life. Yet, if that guy gives her $50 for all of those things then it’s a whole different issue.

Which is why the QAnon stuff, the Pizzagate, focuses on kids. Because you don’t have to go and ask yourself all these questions because it’s children and we know that children cannot consent. Agency, for the most part, is taken out of the equation and so we understand the vulnerability of children. But, again, you know the difference between a 17-year-old and an 18-year-old is 60 seconds.

As you mentioned, if you look at this whole system of racism it’s very difficult to look at a historical, systemic system of oppression that has had no truth and reconciliation process to it. And I think that is what is happening with the sex trade, as well, is that we’re pulled in many directions intellectually, emotionally, psychologically, culturally.

We cannot even fathom that this is a system that is based on economic inequalities, on racial inequalities, on sex inequalities. When you have, for instance, in Minnesota … about 2% of Indigenous women represent[ing] over 50% of people who are bought and sold. African American girls, according to the FBI, over 50% of them are represented as people who are being purchased, predominantly by white sex buyers because … sex buying is very community-based and because there are more white men and because there is this sense of fetishization and racialization in the act of purchasing sex or purchasing another human being, nobody really talks about those racial dynamics.

[Editor’s note: According to FBI reporting, African American girls make up 59% of those under 18 who were arrested for prostitution and 40% of all victims of sex trafficking.]

It’s a conversation that has barely started. But I think that it’s very difficult for people, there’s so much noise around, that it’s really difficult for people to start listening to survivors and say, how can they talk about what they’ve experienced in their life journeys and how that fits into our entire social economic and cultural system, including our political systems and government systems.

Based on your experience, who are the main actors involved in human trafficking?

What people don’t understand is, first of all, human trafficking does not involve movement. You can be born and have lived all your life in one building in the South Bronx and be trafficked. It’s anybody who transfers, harbors, procures, entices, forces somebody into doing something for purposes of exploitation.

Especially now, during COVID-19, a lot of the trafficking is happening from the home, online. A lot of parents are selling their own children on Instagram and Snapchat and other social media. Obviously you have organized criminal syndicates and local pimps who are also involved in human trafficking, but anybody can be a human trafficker, unfortunately.

We also can’t forget that pornography is part of the sex trade. Pornography is just prostitution with the camera in the room. I don’t know if you’ve been following the Pornhub shutdown petition, but yeah that’s a whole different thing, but it also includes many elements of human trafficking.

[Editor’s note: According to Traffickinghub.com: “The Traffickinghub campaign, founded by Laila Mickelwait and powered by the anti-trafficking organization Exodus Cry, is a non-religious, non-partisan effort to hold the largest porn website in the world accountable for enabling and profiting off of the mass sex-trafficking and exploitation of women and minors.]

That’s something that people generally don’t know about. For them, human trafficking is the film “Taken.” Which could happen, but that’s not usual. For us, the most common is the Epstein-type trafficking: you identify any vulnerable person, usually a teenager who is looking for love or attention or a home or food and then start trafficking them for a ready-made market.

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()