How has US debt grown under Trump’s presidency?

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, candidate Trump promised he would eliminate the US debt “over a period of eight years.” He has instead presided over its fastest-ever increase.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused the United States’ debt and deficit to reach unprecedented levels as federal rescue packages have attempted to save an economy that was shut down by the contagion.

By the end of the 2020 fiscal year, the US federal deficit is expected to reach a sum of US$3.7 trillion. The US debt has undergone a similar rise and now stands at some US$27 trillion, an increase of around US$7 trillion since President Donald Trump’s election.

Yet this dramatic growth in the debt and deficit is not the fault of the coronavirus alone. Even before the pandemic prompted massive federal spending amid a significant drop in revenue, President Trump’s stewardship of the economy had seen US federal debt grow at a faster pace than any of his immediate predecessors.

Despite his promise during the 2016 presidential campaign that he would end US debt within eight years, the impact of President Trump’s policies, alongside the unprecedented economic dislocation caused by the coronavirus pandemic, has seen US federal debt reach its highest level in history.

Skyrocketing debt

During the 2016 presidential campaign, candidate Trump promised he would eliminate the US debt “over a period of eight years.” He has instead presided over its fastest-ever increase.

The claim appeared highly unlikely at the time, with US debt standing at some US$19 trillion, but Trump believed that by “renegotiating our trade deals with Mexico, China, Japan and all of these countries that are just absolutely destroying us,” the debt could be reduced significantly.

Trump also believed that tax cuts would stimulate growth in the economy, which could be combined with cutting waste in federal spending to help reduce the debt.

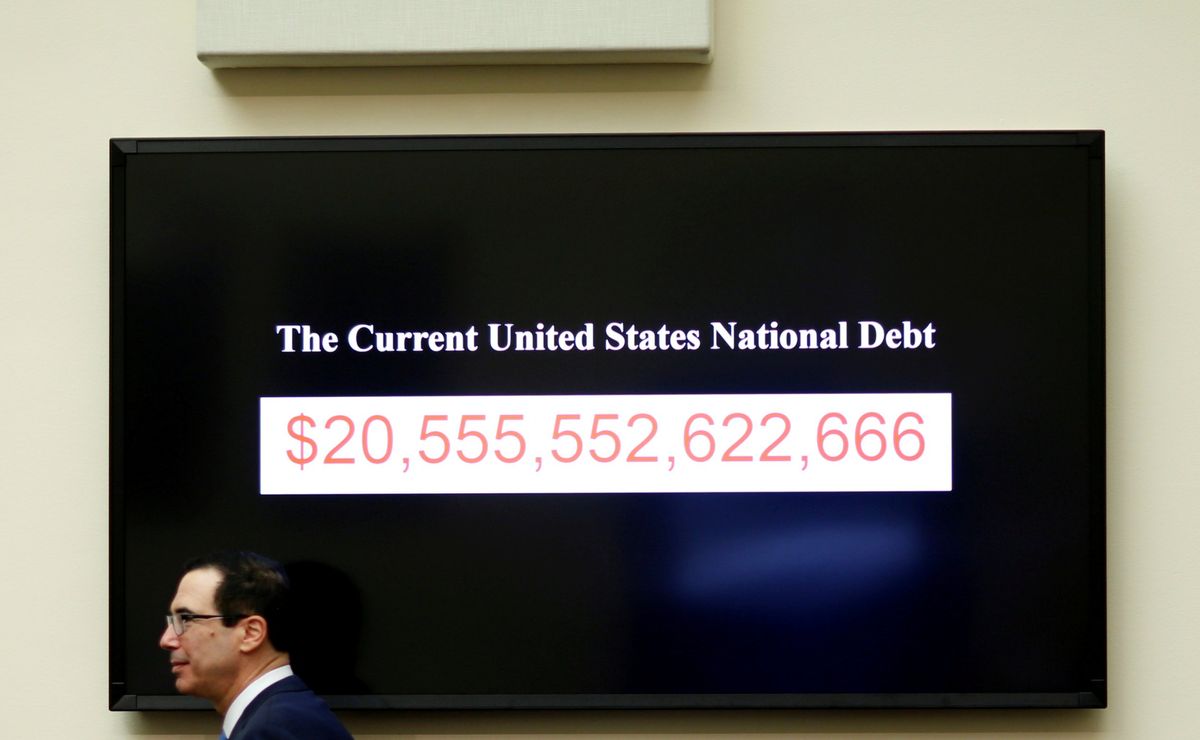

For the first few months of Trump’s presidency, the debt did indeed fall by a small amount. In January 2017, the month Trump took office, the debt stood at US$19.9 trillion and by July it had fallen to US$19.8 trillion.

But this tiny decrease had little to do with Trump’s own policies but instead a US$20 trillion debt ceiling that kept American federal debt below this figure.

Despite the small decrease over the first few months of his presidency, President Trump soon committed to an ever-higher debt ceiling. By September 2017, President Trump had signed legislation that increased the debt ceiling and that month the US debt rose above US$20 trillion for the first time in US history.

This first increase would be a sign of things to come in President Trump’s first term.

The president’s landmark legislation, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, was a hallmark of his and his fellow “supply-side economics” adherents’ belief that tax cuts for corporations and for the wealthy would help to stimulate growth in the economy. Tax cuts would allegedly give individuals and companies more money to funnel into the economy through worker’s wages.

The 2017 act reduced the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% and top individual income taxes were lowered to 37%. The corporate tax cuts were permanent, whereas the individual cuts were set to expire after five years.

Despite Trump’s belief that tax cuts would help to lower the debt, the president has also paradoxically spent more in many areas than his predecessors.

For instance, rather than cutting federal spending to account for the lost revenue from tax cuts, President Trump unveiled a defense budget of some US$936 billion for FY2020, nearly US$100 billion more than the record-breaking military spending in 2012.

The combination of massive tax cuts and no similar cut to federal spending has meant that President Trump’s administration has presided over the fastest increase in the US debt in history.

This is especially ironic given that the debt was previously one of the Republican Party’s favorite topics with which to attack Democratic President Barack Obama before the rise of Trump.

Trump’s policies do not stand alone in raising the debt to unprecedented levels. The coronavirus pandemic, which shut down much of the US economy throughout the spring of 2020 and prompted massive federal relief packages, is also responsible for cutting federal revenue and increasing deficit spending.

As of October 2020, the US debt currently stands at some US$27 trillion, with deficit spending in FY2020 and FY2021 expected to amount to US$3.7 trillion and US$2.1 trillion.

President Trump’s press secretary, Kayleigh McEnany, told Fox News in late September that Trump plans to make the growing national debt a “big second term priority,” but provided little evidence as to the measures he would adopt to reduce it.

The president himself has committed to extending his tax cuts should he win a second term. In August 2020, Trump told a press conference that “if I’m victorious on November 3rd,” he plans to make “permanent cuts to the payroll tax.” Trump’s tax cuts have already caused a massive increase in the debt once and they could do so again.

Debt and daily life

US federal deficit spending and debt have risen to unprecedented levels during the Trump administration. The US debt-to-GDP ratio (the ratio of a country’s debt to its gross domestic product) stands at roughly 136% in 2020. This means that the US debt now amounts to more than America’s economic output in a single year.

This is still far behind other major world economies, such as Japan, which boasts a national debt which is a massive 234% of its GDP, but it is far ahead of China, whose national debt is only 54% of its GDP.

Despite the significant increase in debt presided over by President Trump, the extent to which these figures matter for everyday Americans is debatable, at least for now.

Some experts fear that the US could become stuck in a “debt trap” in the future, whereby high debt slows economic growth, harming the economic well-being of normal Americans, but ultimately leading to more debt as the government continues deficit spending.

Yet, some level of debt can actually help the economy. A government that engages in deficit spending is not necessarily a bad thing, as this spending can go toward contracts and projects that can all help to create jobs and get Americans spending – in effect, recouping whatever the government spent in its deficit.

This is not to say that governments can afford to engage in debt-raising deficit spending all the time. One study by the World Bank has argued that countries whose debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 77% for a prolonged period (as US debt currently does) can experience economic slowdown.

Slower growth can make it harder to make payments on this debt, which can cause a spiraling effect of rising interest payments eventually leading to economic crisis as debt becomes unpayable, which may mean massive cuts to government spending and a massive recession that would hurt the vast majority of the population.

For now, this fear is unlikely to be realized. Foreign countries such as China and Japan continue to buy US debt and lend to America, which helps their exports and helps keep interest rates on the US government’s debt low. So long as the US can afford to service its debt – not necessarily pay it off in full – interest rates and confidence in the US economy will remain stable.

But as Maya MacGuineas, president of the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, has stated, “the debt doesn’t matter until it does.”

For now, the US can afford a high debt and prove to the world that it can continue to service and pay it off. By the time it can no longer do this, however, it may already be too late.

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()