What’s up with all these horror remakes, sequels and prequels?

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

Hollywood has a thing for franchises – and we’ve seen plenty of horror remakes, sequels and prequels in the works lately. If a movie makes money, you can pretty much guarantee that you’ll be seeing more of it (whether that movie was any good or not). Every once in a while, the sequel to a movie is just as good, if not better, than its predecessor (case in point: “Toy Story 2” and “22 Jump Street”). However, it seems that moviegoers have been experiencing franchise fatigue for years. Is there any such thing as a stand-alone movie anymore?

When it comes to horror and thriller movies, though, the concept of the franchise takes on a whole new meaning. It’s hard to find any halfway decent horror flick that doesn’t come with eight sequels, a prequel and a random spinoff or two. The “Halloween” movies, for instance, have no discernible, canonical timeline. There are 12 of them with five different timelines in total. And, well, “Halloween” isn’t exactly the outlier here. Great flicks like “The Blair Witch Project,” “Paranormal Activity” and “The Conjuring” all have spawned many sequels, which may or may not have missed the point of the original film altogether.

In conversation with S.A. Bradley, the creator of the “Hellbent for Horror” podcast and author of “Screaming for Pleasure: How Horror Makes You Happy and Healthy,” we discussed the penchant for franchises within the horror community. Bradley expressed distaste for them, saying: “Myself, I really dislike horror sequels and franchises. I’m not a huge fan of them in any genre, but I think they are detrimental to what makes a good horror film. The element of surprise is essential, and the best horror films refuse to explain away everything or tie everything up with a neat bow at the end.

“Horror gives us a visceral exploration of our most primal anxieties, and the lack of motive or resolution mirrors our real-life monsters and gives us a safe way to find catharsis around them. Sequels are all about answering questions, learning more details, filling out backstories – and I think horror sequels kill what they love, like a parasite.

“Now, with that said, I don’t think that the number of franchises in the horror genre is disproportionate to what you will see in just about every other genre,” Bradley continues. “Horror is a half US$1 billion business, and a recent article in The Hustle showed that the market share of ticket sales for horror films jumped from 10% in 2017 to 18% this year. So, in the uncertain COVID-19 world, horror is what people want to see.

“If people go to see sequels, stand-alone movies will become franchises. Science fiction has ‘Star Trek’ and ‘Star Wars,’ action films have ‘John Wick’ and ‘The Fast and Furious’ franchises and comedies have ‘The Hangover’ and ‘Rush Hour’’ films. The thing that all these movies have in common is that they are wildly popular, and the audience wants more of them. What makes these films popular franchises or what makes them obvious cash grabs is a very subjective distinction, one that might say more about the viewer’s tastes than it does about the movie itself.”

And that’s not even getting started with horror remakes. So. Many. Remakes. “Psycho,” “Scream,” “Carrie” and now “Candyman.” When it comes to foreign horror movies, American producers pounce at the opportunity to remake them for American audiences – even without demand from those audiences. “Train to Busan” and “Let the Right One In” have been optioned for American remakes; “Let Me In” was released in 2010, and “Train to Busan” was optioned by American filmmakers earlier this year.

Out of all genres, why do horror franchises seem the most prominent? What is it about these movies that create opportunities for continuous exploration? And why do we keep paying money to see what we’ve effectively already seen before?

Horror fanatics and cult followings

If there’s a horror fan in your life (or if you are that horror fan), then you’re probably familiar with the kinds of people who really love the genre. It’s a strange phenomenon, the courtship between scary movies and the watchers of them. Like, who enjoys being scared?

Maybe one of the reasons that horror films do so well as franchises, why horror remakes and sequels are constantly in the Hollywood queue, is that horror fans will spend money to see them. This is the case even for bad horror movies, which spawn cult followings like nobody’s business.

The iconography of horror movies and franchises certainly plays a part. It’s challenging to guarantee something will scare an audience – how do we know that a new idea will garner the same screams as an old one? After all, Freddy Kreuger and Michael Meyers have already shown they can trigger feelings of fear, so let’s keep bringing them back.

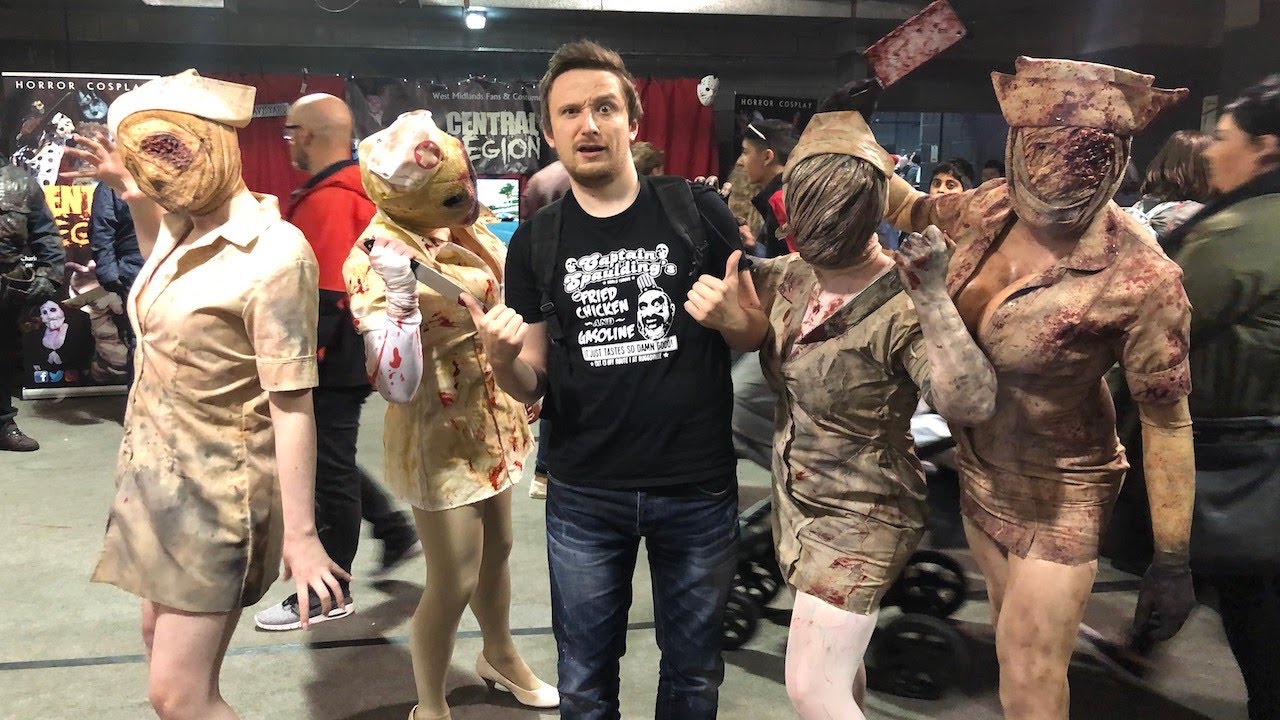

So many franchises have spanned decades at this point. Some horror fans have noted that the characters, concepts and villains have “been a constant presence in so many people’s lives,” which garners steady interest in new installments. Horror franchises somehow create symbols and lore that stay relevant within a culture. And, around Halloween every year, you’re bound to see references to Pennywise and Carrie, to the girl from “The Ring” and Hannibal Lecter and Norman Bates. What scares us stays with us, it seems.

Bradley has another theory. “I think that horror understands the outsider and the misfit,” he explains. “In the world of mainstream films and entertainment, the horror movie is the outsider and the misfit. I can’t speak for all horror fans, but I can say that many of the folks that I meet at conventions and film festivals tend to be people who dealt with a lot of trauma and alienation early in their lives. And so many of them found comfort in the horror movie.”

For decades, film theorists have written about the horror genre and catharsis. There’s something about releasing these pent-up anxieties and negative emotions through a “controlled” scare that helps us find relief from our psychological baggage.

“For some, it helped them work through some heavy emotions from a safe distance,” Bradley points out. “For others, they related to the monster and sometimes felt seen for the first time. And for many, the horror movie helps them feel comfortable in their own strangeness and be OK with themselves. A lot of people that I know had a bad first act in their lives, but now they are having a fantastic second act. Many of us find a surrogate family in the horror community.

“When you find something that speaks so deeply to you, you become a fan and you want to see everything you can, warts and all. You mentioned cult followings for films that aren’t “good,” and I think that’s a byproduct of being an outsider and the misfit and yet finding acceptance from others just like you,” Bradley explains.

“I have a group of friends who get together to watch ‘turkeys,’ horror movies that are at times absurd and ineptly directed. We laugh a lot, but we don’t mock those movies because we can tell these misfits had their hearts in the right place. These movies are still entertaining even if not in the way they were originally intended to be. Good or bad, the horror movie is outsider art for outsiders.”

Horror as social commentary

Few genres can pull off social commentary as well as horror can. The allegorical nature of these stories has been the case for centuries – even before movies were around. Books like “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” explore the anxieties of their times. As horror films took off, the genre has continued to explore societal woes; think about the particular brand of woke-racism that Jordan Peele alludes to in “Get Out,” and the class critique of “Ready or Not.”

Academics have explored this occurrence in what is aptly named “monster theory.” Essentially, monster theory suggests that what scares us in fictional media, especially in speculative or supernatural media, is revelatory of our cultural values or realities. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen collected academic essays from his contemporaries to form the book “Monster Theory: Reading Culture,” which served as the landmark exploration on this idea, with different case studies being focused.

That being said, do horror filmmakers owe it to their audiences to keep their movies socially relevant? The remake of “Candyman” certainly buys into the idea. When the original film was released in 1992, it heavily relied on themes of social class and race relations in Chicago (and the United States as a whole). The new version, released this year, is both something of a remake and a sequel, bringing in themes of gentrification and skepticism of media as an industry.

Was this remake strictly necessary in terms of the literal conflict of the movie? Probably not. However, the 2021 “Candyman” is a prime example of a horror film re-imagined to suit the socioeconomic conflicts faced by millennials and by Gen-Z, for whom the first iteration was certainly not made.

It is somewhat frustrating to see the same ideas played out over and over again on screen rather than fresh stories and concepts. Still, it’s also compelling to see how different filmmakers choose to represent complex contemporary issues through these age-old frights.

We pose a complex question to Bradley: “Do horror franchises owe it to their audiences to continue to attempt staying relevant to the world as it is today, rather than it was when the first movie came out?”

He replies: “I think it is more accurate to say that audiences owe it to the horror film to recognize how horror is always relevant to the world as it is today. Horror is tailor-made for allegory, metaphor and parable. Its purpose as a storytelling style is to poke at our anxieties whether we are aware of those anxieties or not. Consciously or unconsciously, horror is constantly commenting on our culture and our society; we just might not like what we see.

“It is no coincidence that right after the 2004 Abu Ghraib torture scandal happened and our government turned a blind eye to torture, that we had the birth of James Wan’s ‘Saw,’ Eli Roth’s ‘Hostel,’ and other ‘torture porn’ films. I like to tell people that if you really want to find out what the major social anxieties of any decade were, go back and look at the exploitation films, the trashy horror films – not just the critically acclaimed ones. Because those B-movies lived or died on whether they could find a hot button to press, something to get Middle America’s attention.”

“Horror movies don’t always play nice, and they don’t always show us in the most flattering light, but what they have to say is always relevant,” Bradley continues. “Horror is the cautionary tale, and it is as ancient as storytelling itself. Why has it endured so long? It has endured because we need it. It’s not a social need, it’s not a cultural need, it is a human need. And no matter how many slings and arrows we throw at it, horror will be there for us when we need it. And, sooner or later, we will need it.”

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()