When it comes to tackling social injustice, the sheer scale of the issue at hand can be overwhelming. These problems don’t always directly affect us but are hidden and require our proactive attention. But, then, even once we face an issue, it can be challenging to know where to start with efforts to eradicate it.

We’re often told to start small – and that’s exactly what the 24 Hour Race did.

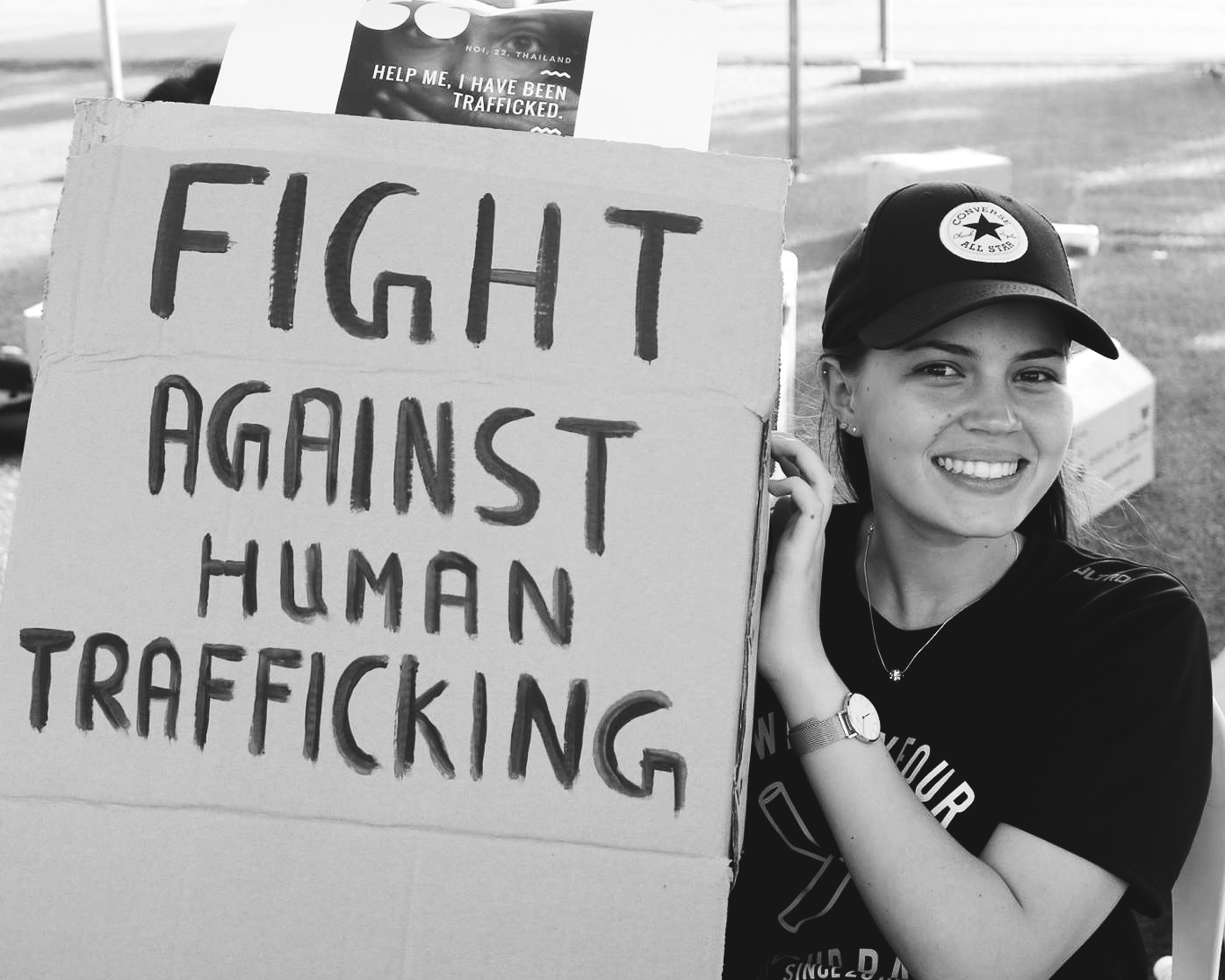

The 24 Hour Race was founded in 2010 by Christopher Schrader when he was a 16-year-old student in Hong Kong. He wanted to bring together students interested in endurance sports and philanthropy for a good cause – a global fight against human trafficking.

Gathering young people willing to lead and run this charitable 24-hour-long endurance relay race, collecting fundraising money and using this money to help NGOs and projects related to human trafficking grew into the 24 Hour Race organization that exists now. Since its creation, the 24 Hour Race has expanded into 23 countries.

TMS spoke with Daniel Hestevold, the chief operating officer of the 24 Hour Race, about the organization’s initiatives against human trafficking and its path moving forward.

“The 24 Hour Race movement is one of the largest student-led movements in the world that’s fighting modern day slavery,” explains Hestevold. “And in short, we’re basically a generation of young people no longer tolerating a world where slavery’s allowed to exist.”

The issue of human trafficking

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime defines human trafficking as the “recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of people through force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them for profit.”

“Out of the 40 million slaves, about 50% […] would fall under the category of forced labor,” explains Hestevold. “Unethical supply chain issues is probably a term that more people are familiar with, which generally refers to some sort of slavery throughout the supply chain cycle,” Hestevold explains.

“It’s hidden. What you don’t know is that it’s the fastest growing criminal activity in the world. It’s annually a US$150 billion company for 40 million slaves. And what the problem is, they’re such big numbers that they become highly impersonal.”

Aside from the issue of human trafficking within the supply chain, Hestevold also mentions other cases of forced labor, including slavery within the sex industry and debt bondage, that each illuminates the social injustice that human trafficking imposes upon our world.

“In many societies around the world, it’s embedded into the society in that there are entire villages and towns, cities in third world countries that are completely reliant on the income of slaves,” says Hestevold. “Whether that’s a mom or a father working at a sweatshop, or whether it’s sending kids to sweatshops, or whether it’s a mom working a daytime job as a sex slave, you know? There are societies that are completely reliant on the income of slaves.

“By nature, it’s hidden, it’s dark, it’s not in your face. And I think that’s one of the most difficult parts of raising awareness of slavery is that, well, where are they? If it truly is as bad as you say, then why haven’t I known about it?”

How does the 24 Hour Race tackle modern slavery?

Founded in 2010, the 24 Hour Race movement started simply – as an endurance race funding teams of eight from different schools to run for 24 hours straight. Now known as the Running To Stop The Traffik (RTSTT) initiative, the 24 Hour Race has garnered much traction and success in fundraising.

“Little did we know that the concept of the 24 Hour Race was one that millennials or young people really connected with,” recalls Hestevold. “Fast forward 12 years now, in 2022, we have 23 countries around the world with the 24 Hour Race movement present, which means that every year thousands of young people are taking part of this movement to end slavery.”

However, the organization wasn’t immune from the effects of the pandemic. Though the pandemic did bring some changes to how the 24 Hour Race was operating, it didn’t stop them from pursuing their mission.

“We were already using Zoom and all these kinds of tools before the pandemic because we were a Hong Kong-based charity with global operations around the world, Hestevold remembers. “And since we don’t have staff in all these places, we have students, we need to communicate with them. So using Zoom and stuff was kind of just the world catching up to us, it felt like.

“But what we didn’t expect was to have to host our races virtually, which led to a lot of races being canceled, including Hong Kong, which was particularly tough for us. I think last year we held two in-person races only – one in Singapore, one in Cardiff – both kind of a small-scale version of the races. But we are slowly getting back into the rhythm of having in-person races.

“Unfortunately, this year we can’t do one in Hong Kong in-person. So I guess the negative impact of the pandemic, the bad side of the sword has been the impact financially,” says Hestevold.

Despite some setbacks during the pandemic, the organization has looked to create change in other ways, like with a new program for universities.

“Last April, we launched our university expansion program, which was essentially reaching out to 24 Hour Race alumni who are now in universities and basically saying, ‘Hey, do you want to bring the race to your university? If so, get in touch with us, and we’ll try to make it happen.’ And that was a huge success. We had almost 150 applicants to bring the race to their city,” says Hestevold.

The 24 Hour Race sets out to combat the upward trajectory of human trafficking, not only through the RTSTT initiative but through other initiatives, partnerships and workshops. The money collected from fundraising goes into various projects and partnerships with NGOs and firms.

Some examples include a partnership with the SUKA Society based in Malaysia, which supports victims who have escaped trafficking, and partnering with a pro bono law firm that helped ban the exploitation of Nepalese children in India within the circus industry. The 24 Hour Race also partnered on a project with The Exodus Road that released 326 victims from slavery and put 177 traffickers behind bars.

In addition to these projects, the 24 Hour Race places great value on education and awareness. From leadership to educational programs to mentorship workshops, the 24 Hour Race empowers youth in learning and contributing to the cause all around the world.

Youth empowerment and contribution opportunities

Hestevold himself started at the organization through a race. “I was involved with the first races [back in 2010], and I was absolutely blown away by the fact that this was completely student run,” he says.

“Everything you saw on race day [and] leading up to race day was completely run by students, and those are your student directors, your committee members, your team leaders, and it was very impactful to me that young people can actually make such [a] tangible impact at such a young age,” reflects Hestevold.

In addition to these leadership programs, the 24 Hour Race provides other initiatives for students to help solve the issue of modern slavery. The mentorship workshop aids students in taking on leadership roles in fighting human trafficking. Youth empowerment conferences are also hosted in schools to educate students. An “incubator” initiative helps students pitch their own projects for combating human trafficking, and the 24 Hour Race can mentor a project for three to six months.

These initiatives build up conviction in young people to fight against slavery while also honing their practical skills and demonstrating the importance of actively including young people in global issues.

“We truly believe that 10, 15 years down the line, if we’re able to kind of increase the numbers of people that we send out into the world, we can make a real long term impact, a big dent on slavery,” says Hestevold.

Even if you aren’t actively participating in the 24 Hour Race’s initiatives, Hestevold underlines the importance of education and raising awareness (even on a small scale) to tackle modern slavery.

“We encourage people to take the education of slavery seriously, in that every person around the world has some sort of slavery footprint,” Hestevold says.

He also emphasizes the importance of being accountable and aware in our everyday lives. You can contribute to the fight against human trafficking with your mindset. As simple as this may sound, it isn’t always easy to confront ourselves and others regarding a slavery footprint. But being accountable and self-aware is essential to reducing our overall slavery footprint.

“We challenge typically our student directors because we stay in touch with them, and when they start their new job to do some due diligence, to look into their company,” Hestevold says. “‘Are we buying and sourcing material from ethical places? Are we investing or divesting from unethical businesses?’ Ask the hard questions, do your due diligence, do some research, find out what you personally, what your family and what your job [or] your company footprint is like.

“And then if you’re able to make changes, make changes. But beyond that, it’s about, I guess, just stay alert, stay aware, stay committed to bettering the life of people that you will never meet.”

What’s next for the 24 Hour Race?

Looking forward, the 24 Hour Race will continue to empower young people in making a change. However, there are some ongoing difficulties due to the pandemic. For example, only two in-person races out of 26 planned were hosted in person last year, while other races had to be hosted virtually.

Working against these challenges, the 24 Hour Race will focus on what it does best – student leadership initiatives and education programs – and strengthen its presence in the many cities in which it operates – a number that continues to grow.

“We’re kind of laying the foundations again, in all of the cities that we’re in, old and new, so that the next academic year can kind of hit the ground running,” says Hestevold.

“It’s been a lot of dirty work throughout COVID, throughout the pandemic, and we’re really keen on just streamlining, making everything sharp, making everything clean, making all the cities really, really strong so that we can hit the ground running again next year and make a bigger impact because more cities, more awareness, more fundraising, more youth [are becoming] a part of this movement.”

Comments ()