What is at-home brain stimulation, and does it work?

At-home brain stimulation could be the next big thing for treating mental-based problems and boosting brain performance.

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

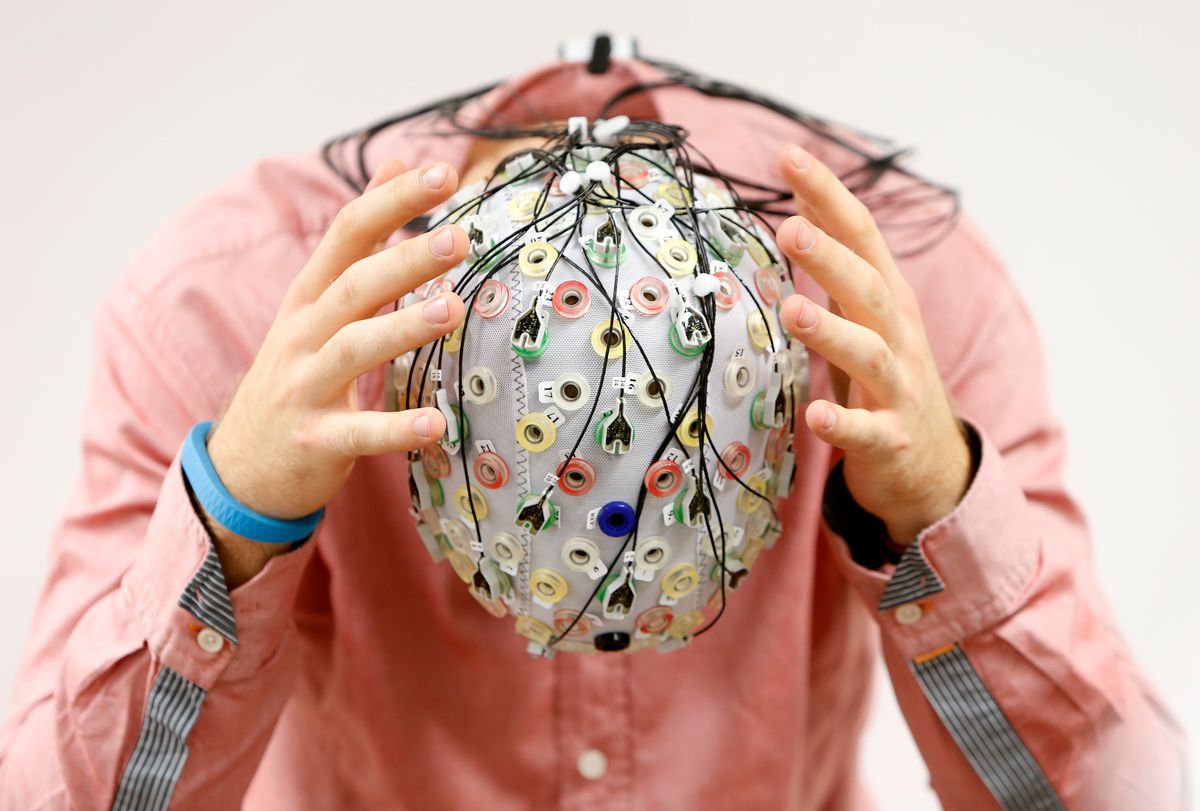

At-home brain stimulation could be the next big thing for treating mental-based problems and boosting brain performance. Specifically, we're talking about transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which involves wearable headgear that delivers a low electric current to the scalp. Usually, users get a fixed current between 1 and 2 mA. Then, the electrodes from the device send electricity into the brain.

But how does tDCS affect brain functioning?

Right now, there's growing hype around tDCS for treating conditions like depression, ADHD and even Alzheimer's disease. The actual science behind how electricity affects the brain is still in its early stages. The idea is that electrical stimulation will manipulate the electrical currents already running through your brain at any given time.

"Depression and anxiety are the top two indications for people," says Anna Wexler, an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. "But other reasons people used it for were for enhancement, so to improve focus, to improve memory, things like that."

And some people have started self-administering tDCS at home. You can buy a tDCS device for anywhere between US$50-$500 (but we're not necessarily saying you should – we'd prefer you take that advice from a doctor). In the last decade or so, there's been a spike in the popularity of these at-home tDCS devices. Before, this kind of treatment was only used in labs and hospitals.

Some scientists aren't too happy with this development.

"We are talking about injecting electricity into someone's brain. Someone could get hurt," says Robert Reinhart, a neuroscientist at Boston University. "We need to better understand what these tools can do including any unintended consequences they may have."

And tDCS has its skeptics.

"What they've found afterwards is that tDCS is super hard to get right because you have to account for so many parameters. You have to account for things like whether that person drank coffee that morning. You have to account for the skull thickness. You have to account for all of the stuff," explained Sally Adee, a science and technology journalist, on the podcast Fresh Air.

Comments ()