A new brain implant shows progress in helping recovery from traumatic head injuries

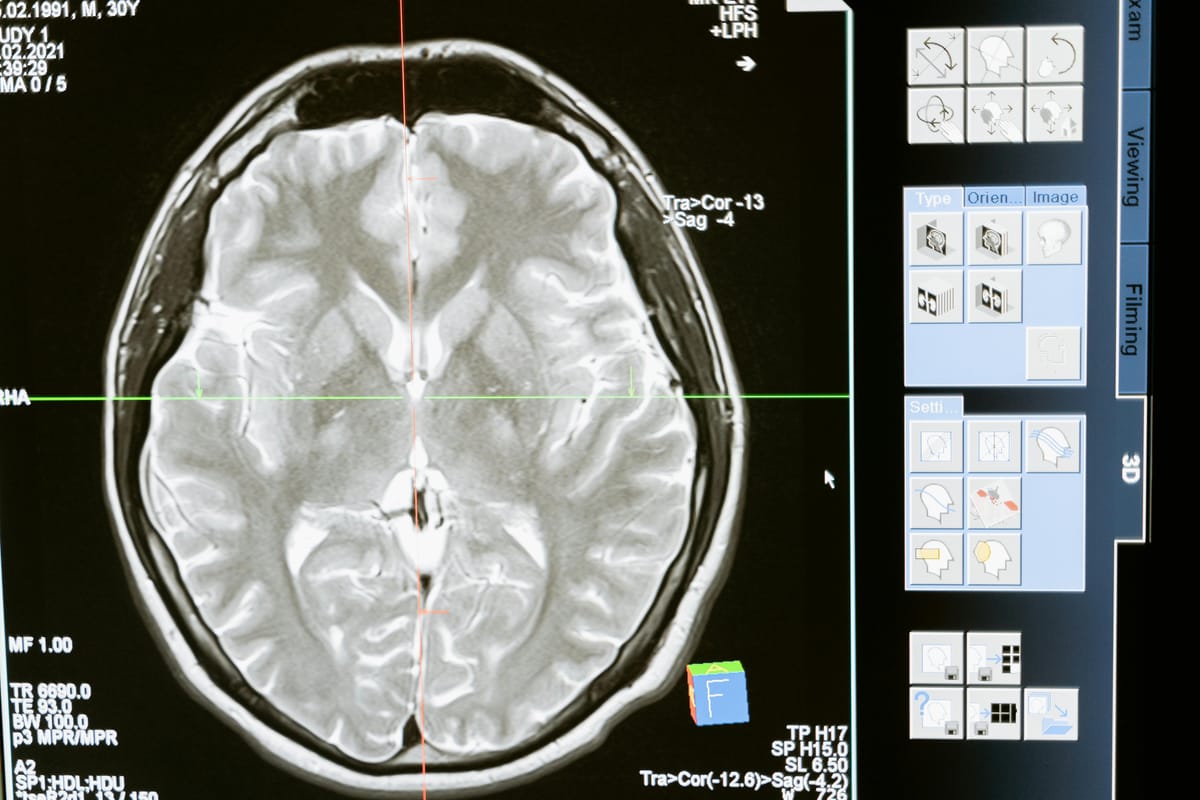

The research team designed a brain implant to stimulate the thalamus brain region, which is associated with alertness, learning and memory, plus our level of consciousness, using small electrodes.

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

When someone suffers a traumatic brain injury, they can sometimes get damage in their frontal cortex. When that part of the brain isn’t working right, a person can experience limitations when it comes to planning, focus and self-control – which makes it hard to do things like go to school, keep a job or even go on dates.

“One of the major problems is that there really are no effective therapies for traumatic brain injury,” explains Dr. Jaimie Henderson, a neurosurgeon at Stanford University.

Stanford Medicine has been conducting research for years with people who have suffered this kind of brain damage. Dr. Nicholas Schiff got an idea for how to treat this condition after being part of a project that used deep brain stimulation to help someone in a “minimally conscious state” become more aware and responsive back in 2007. In 2018, Schiff started working with Stanford and Dr. Jaimie Henderson on a study to see if this kind of treatment might help people suffering from frontal cortex issues after experiencing brain injuries.

“What we didn't know, of course, was, would this work in people who had moderate to severe brain injury?" recalls Schiff in an interview with NPR. “And if it did basically work the way we expected it to work physiologically, would it make a difference?”

The research team designed a brain implant to stimulate the thalamus brain region, which is associated with alertness, learning and memory, plus our level of consciousness, using small electrodes. They worked with five patients who’d experienced their injuries a while ago but who were dealing with chronic mental effects. The operations started in 2018. Since then, the researchers have kept up with their patients over the years, all showing cognitive improvement since receiving the implants. On Monday, Stanford released this small study, which will need to be tested in larger clinical trials for a while before this treatment would become more widely available.

“I can be a normal human being and have a conversation,” Gina Arata, one of the patients involved in the study, says. “It’s kind of amazing how I’ve seen myself improve.”

Comments ()