Voices: A doctor’s-eye view of COVID-19 in the Ohio Valley

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

The Ohio Valley was a coveted bright spot amid dark and dismal news as the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the USA. It had deftly parried the waves of outbreaks that had ringed the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and most everywhere in between, managing a balance between aggressive infection control and sustained economic activity. It had beaten back the travel-borne microbial invasions that had pierced the defenses of other major US population centers and was remarkably free of the plague that had brought misery nearly everywhere else.

Until it wasn’t.

The gathering storm

I was based in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County when the tsunami finally came. I was a doctor and a researcher with an M.D. and Ph.D. in hand, trained at Harvard Medical School and MIT in Boston, shifting over to L.A. and the West Coast, the Rockies and the Great Basin before recrossing the Mississippi to settle back on the Eastern Seaboard. I eventually landed in Western Pennsylvania, throughout the winter and spring of 2020 a seeming oasis of tranquillity, even as the state’s eastern half was ravaged by the horrid toll of the novel coronavirus.

I continued my well-established dance of clinical and research work while surrounded by disquieting hints of something lurking in the shadows, almost tasting the metaphorical clouds of the calm before the proverbial storm.

The cities and towns of the fertile Ohio Valley seemed to have the Goldilocks Touch. We had a balance of major urban centers surrounded by out-of-the-way tracts of open land hugged by the Appalachians and the Three Rivers – among the best medical and scientific hubs of North America, yet without the global hubbub of international magnets like New York, L.A., or Boston, with an unnerving vulnerability amid a border-hopping pandemic.

I went through each day focused on the tasks at hand, all the while quietly absorbing the unsettling signs and colleagues’s sporadic stories of the “mystery illness” cropping up in some patients streaming into our hospitals in January and February. At the time, there was little else we could do.

Up until around the middle of March, one of the most precious commodities for our modern era – fast, reliable tests for COVID-19 – was practically a luxury item throughout most of the US. By now, the bitterly rueful retrospectives have amply documented America’s missed opportunity in those pivotal early months. China had published the genomic sequence of the novel coronavirus in January, and labs in that country, Germany and South Korea quickly set to work designing accurate COVID-19 tests that gained the World Health Organization’s seal of approval. But the powers that be Stateside insisted on designing and manufacturing our own tests, which became fraught with a series of costly delays.

Still, it seemed, the nightmarish scenes from overseas of vast city centers subdued into ghostlike silence or the recently deceased loaded onto refrigerator trucks for want of morgue space – those were mere fever dreams from faraway nightmares. They were eerie omens from Over There that would, nonetheless, remain as mere forebodings from distant lands, never materializing on our pristine land sealed off by two oceans, historically blessed with protection from invaders near and far.

It can’t happen here

“It can’t happen here,” was the prevailing attitude, and our collective frissons of anxiety – that palpable fever in our fellow passenger, that inexplicable loss of smell in the otherwise healthy kid in the waiting room across the hall – were quickly dismissed as fear mongering. We were somehow different from the Chinese and Italians who had been overwhelmed by the stealthy new plague. We were more resistant to infection, and even if we weren’t, our health care system and technology were far superior.

I was one of the medical voices in the wilderness raising cautious objections about such conclusions, pleading in letters to the editor and other forums for mass testing to be expedited and implemented. I began to explore novel treatments myself, using weekend downtimes to apply a bioinformatic drug discovery system I’d developed to tease out undiscovered therapies.

Slowly and creepingly, though – and then with abrupt ferocity – that veil of complacency was pierced.

Cities on the two coasts began to succumb like dominoes to the new plague. Seattle, then San Francisco and L.A. and then, alarmingly, the two Gothams to the east of our lovely valley – New York and Philadelphia – fell prey to the insidious, invisible foe. COVID-19 brought much of the Northeast to a screeching standstill.

Lacking an airport with the international profile of our coastal peers, we seemed to have dodged a bullet in the Ohio Valley. Our case load remained low even as Philly was seized by a blitz-like panic. Pennsylvania’s governor Tom Wolf and his respective counterparts in Ohio and West Virginia, Mike DeWine and Jim Justice, cast a wary eye as the waves of the pandemic joined into a sweeping tsunami.

Lockdowns were organized on a county basis, initially sparing the Ohio Valley until the dreaded case number tallies began their slow but inexorable climb. Soon enough, whether through consultation or simply a common conclusion reached through independent contemplation, all three officials had extended the shutdown to our neck of the Appalachian woods.

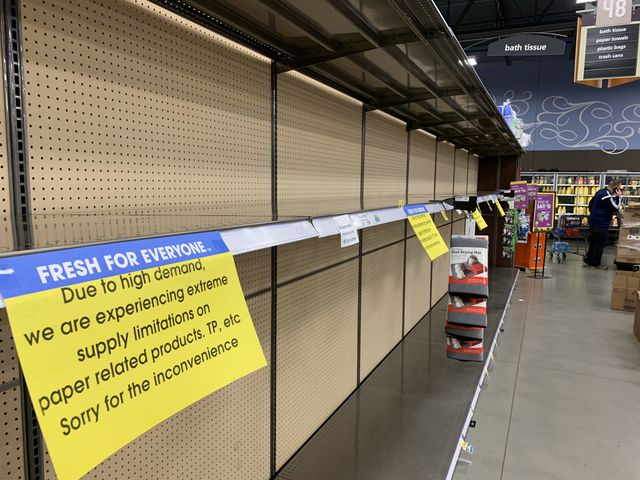

Empty shelves and gnashing teeth

It’s one thing to catch news reports of department stores and grocery providers stripped bare in distant counties, empathizing with the locals but relieved to know they’re reports of happenings from a safe distance away. It’s quite another when it happens to you.

Cupboards and store aisles across the urban triangle of the Ohio Valley, from Pittsburgh to Cleveland to Wheeling, West Virginia, were rapidly denuded of their fresh items barely an hour or two after each twice-weekly restocking. It went far beyond the iconic disappearance of bath tissue, hand sanitizer or paper towels. For me and my close friends, a topic of dark humor was how the shops in different cities each seemed to have their own representative article that was chronically out-of-stock as soon as mere whispers of a lockdown hit the airwaves.

In Pittsburgh, for reasons we could never quite pin down, it was peanut butter. My girlfriend, in town visiting from the West Coast, had done a de facto tour of the local supermarkets to grocery shops and eased my schedule pressures amid long hours in the hospital. She visited the local Aldi and a couple in the outskirts of Allegheny County, several Giant Eagles and Family Dollars, one boutique grocery after another – but peanut butter had become a fabled lost item, so hard to come by that it had fostered its own black market on Craigslist, WhatsApp, and TikTok.

For our northerly neighbors up in Erie, Pennsylvania, it was bottled water and duct tape. Clevelanders seemed to be perennially short of breakfast cereal and canned goods (both for us and our furry friends), while our West Virginia compatriots in Wheeling seemed to be chronically short of fresh produce. And everyone was short on ramen noodles. If we ever have to face a zombie apocalypse, you’ll know it’s bad when the ramen shelves are picked clean.

With all that said, it seems people were able to cope with the shortages decently in the broader Ohio Valley and northern Appalachians, at least for a while. Instacart and other grocery and restaurant deliverers helped to minimize the potential for Twitter-worthy supermarket scuffles as the pandemic’s restraints cut more deeply. Hoarding became a social faux pas, and in any case an underground barter economy sprang up in short order to help remedy some of the most acute deficiencies.

But as the lockdowns (both formal and impromptu, as people hesitated to go out much) dragged on, there were times when tempers began to flare. In perhaps the most conspicuous case for which my own eyes served witness, a lone can of soup became an object of more bitter tussling than the titular One Ring in Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings,” occupying an otherwise bare shelf during the hotly-contested just-after-work hours.

And petty brawls and brouhahas didn’t break out from such shortages alone. Mask wearing itself, unfortunately, soon morphed from a science-driven nugget of public health guidance into the visual token of a bitter ideological divide, a stamp of one’s political tribe. With predictably ugly consequences, especially in a region full of Battleground States and fraught rhetoric.

One of the most notorious such incidents in the whole nation took place at the Mootown Creamery in Berea, Ohio, which became a bizarre hill to die on for several zealots who openly raged at the shop’s teenage girl employees for having the audacity to wear masks to protect their patrons while serving ice cream. Yes, this actually transpired.

The open door creaks shut

Our one consolation in the Ohio Valley is that our social springtime sacrifices had not been in vain. We had kept COVID-19 at bay far better than most other population centers in the country. We could safely reopen our restaurants, our gyms, our bars and meeting halls and our schools and summer camps. It wouldn’t be easy, but countries like South Korea, Vietnam, Austria, the Czech Republic, Greece and Argentina showed that it could be done if undertaken with discipline and vigilance. And for a while things went according to plan. Alas, the best-laid plans…

If there was one ironclad rule for a post-lockdown reengagement of the economy, it was that mass gatherings were Petri dishes on a macroscopic scale and could occur only with the most rigorous precautions. Masks, social distancing, fanatical cleanliness and a predilection for the outdoors (with rapid disinfection of surfaces from the sun’s ultraviolet caresses) – only these would keep the deadly plague at bay. But it was not to be, and this time, the Ohio Valley would become an epicenter of its own.

The isolation and lonesomeness provoked by the invisible foe gave way, as these things often do, to an uncontrolled embrace of relative freedom when the lockdowns were relaxed. Indoor bars were filled to the brim, pool parties took off with mask exhortations cheerfully ignored and mask demands themselves led, in bitter irony, to angry congregations in public buildings by those opposed. Meanwhile, the globally disseminating images from Minneapolis of Officer Derek Chauvin snuffing out the life of George Floyd provoked an outburst of resistance from coast to coast, with the tear gas canisters from riot police serving as an unwitting catalyst for further spread. Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Columbus and Wheeling were all caught up in the various upheavals.

Then the news got worse. By June of 2020, it had become abundantly clear that the lethality of COVID-19, with a death rate at least 20-30 times as high as the seasonal flu, was merely the fearsome tip of a perilous iceberg.

Clinical research in Germany and several Asian countries had demonstrated that the coronavirus’s most alarming threat, in terms of sheer ubiquity, wasn’t death as much as disability. Even mild or asymptomatic cases were associated with a frighteningly high level of persistent damage to the lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, central nervous system or gut – by some studies more than three-quarters of those affected. Kids and young adults, once thought to brush off COVID-19 with barely a scratch, were not spared. If this malicious microbial genie got out of the bottle, and if indeed these organ and tissue dysfunctions were persistent (what we call long-term sequelae in medical lingo, like viral myocarditis or dysautonomia), potentially an entire generation was facing a grim toll on its well-being and working capacity.

These updates, unnerving enough in the abstract, soon delivered a more personal jolt. Several friends and medical colleagues in other states had been affected, with two winding up in ICUs, mechanical ventilators doing their breathing for them. And then things really hit home.

I’d begun struggling myself earlier in the year, getting winded rapidly and feeling pain and fluttering in my chest. It wasn’t the first time I’d found myself gasping for air. As a young doctor in California, I’d been in the epicenter of a pertussis epidemic – the agent behind whooping cough – and sustained chronic obstructive sequelae to my own lungs from an exposure on duty, putting my clinical aspirations on hiatus.

Now I was in another hot zone for an even deadlier pathogen, and with the additional hits from a tandem assault by two pneumonias, my heart and lungs were bearing the scars of a prior battle before widespread coronavirus testing had become available. Such battlefields now raged throughout the Ohio Valley, with cases surging in vulnerable population centers, from Pittsburgh to Columbus, that had once seemed relatively unscathed. Once again the Valley began locking down, this time with a more fearful fervor, and soon enough the downtown diners and dives, the phoenix-like survivors of a Rust Belt renaissance, had become silent.

Ghost towns and G chords

Thus has the summer of 2020 in the Ohio Valley taken on its signature sound: a haunting, often surreal tone of intermittent silence, punctuated by tentative bursts of activity that quickly vanish back into the ether of an eerie stillness. There’s a strange paradox to it all. The people are still here, the homes still ping messages from the ubiquitous Zoom meetings on residents’ desktops, newspapers still pile up at doorsteps.

Yet the Valley has the spooky vibe of a clutch of self-aware ghost towns, all whispering inscrutability to each other like the mysterious nowhere-lands of an unsettling short story by Robert Chambers, H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur Machen and other disciples of Edgar Allan Poe. It’s a sensation that’s hard to describe, but unmistakable to the locals and visitors and semi-itinerant nomads like myself somewhere in between.

The malls and office parks are, at most, a quarter filled at the heart of the day and seem to have a weird hiss to them with subdued activity murmuring in the background.

Rest stops stand virtually abandoned, with calls for social distancing etched in glaring yellow caution tape around the restrooms and restaurants nearly all shut down, aside from a stalwart or two still catering to the sparse stragglers that occasionally stream in.

Sports venues, summer schools, camps and college campuses stand in taciturn witness of their near-abandonment, humming only with the rustle of airy drafts and birdsong that pierce the summertime air.

Grocery stores and other essential shops keep doors open, but the once defining banter of patrons is nowhere to be heard, replaced largely by the nervous glances of a diminished quorum of masked patrons darting their eyes about on the lookout for exposure risks.

No doubt there are silver linings, most notably the drop in traffic that had once choked the William Penn Highway or the Pennsylvania Turnpike even outside the confines of the a.m. and p.m. rush hours. But the weird post-apocalyptic vibe and collapse of even basic social interactions slowly gnaw at one’s sense of well-being and peace of mind.

We’re all here, in each other’s midst, yet not here at the same time.

As the summer rolled on, I was finally able to take solace in two critical anchors with both personal and professional significance. I got the sweet news that my scientific paper on drug repurposing for COVID-19 – a shotgun marriage of my skills as a physician and my incessant tinkering as a computer programmer and researcher – had borne fruit and was accepted in a major journal. Even amid the ongoing ravages and horrors of this persistent pestilence, I was making a small but critical contribution to combating its power and terror.

I also took heart in the melodies and chords I was stringing together on my small but sturdy Canadian Art Lutherie guitar. It was one that I’d begun strumming at the tender age of 9, eventually blossoming into the instrumental nucleus of my own alternative rock and 90s revival band, J. Wes Ulm and Kant’s Konundrum, with a hit debut EP and a major award-winning music video for our first major release, “A Hustler’s Tale.”

Unsurprisingly, any concerts, shindigs, festivals and open mics had been placed on indefinite hiatus since February 2020 had announced its presence on the pages of my refrigerator calendar. But amid the loneliness and uncertainty of this grim year and its Lost Summer, when even my closest friends and girlfriend were confined to the electronically-transmitted sounds of a video call on a mobile device screen, my music once again beckoned out and filled me with a sliver of crucial optimism.

I began once again to settle into a groove and write songs, building on my second EP in progress to craft the foundations of a third. My voice and fretting hand had been weakened by my own respiratory battles and recordings were a challenge, but gradually the tunes began fighting their way out nonetheless.

And so here I stand, at the start of a still-uncertain autumn. Like my colleagues, friends, and neighbors, gripped with that uneasy partnership of fear and cautious optimism, cautious with every step and breath, but quietly hopeful of finding my path amid this new normal.

This Voices story was written by doctor and medical researcher J. Wes. Wes is also a musician and an 11-time award winning filmmaker currently based in Pittsburgh, PA.

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()