Study: The US is a breeding ground for a growing diversity of diseases

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

The research could help scientists predict where and when the next pandemic will arise, but it is also a warning that nations will need to halt the destruction of natural habitats.

A recent study out of the University of Sydney in Australia has added to the growing body of evidence suggesting that humans are increasingly responsible for viruses like SARS-CoV-2 (or COVID-19). The study, published in March, found that countries with higher incomes, higher population density and greater forest coverage, such as the United States, are likely to have a higher diversity of such diseases.

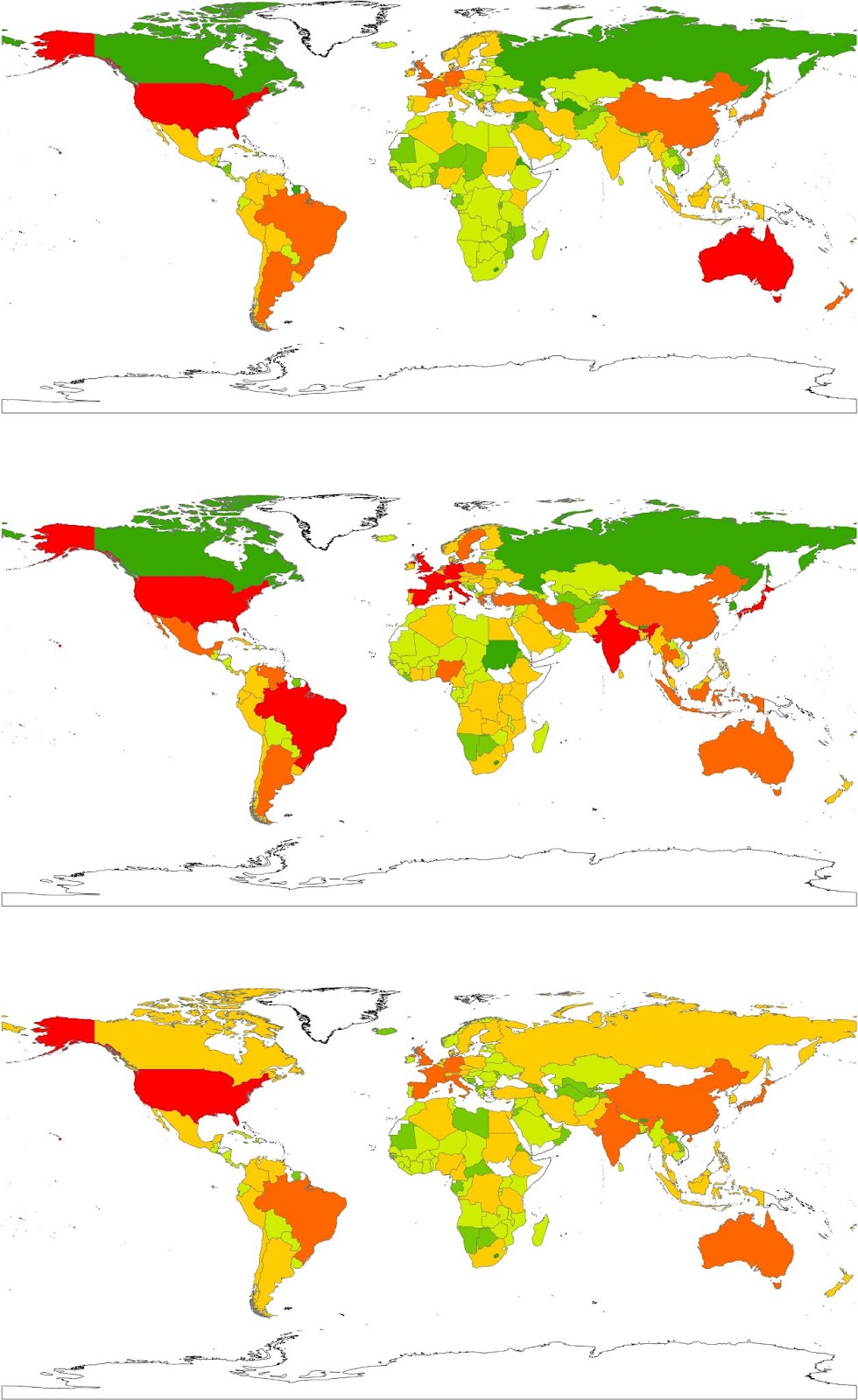

The study used modeling from the Sydney School of Veterinary Science to look at the diversity of three types of diseases: human, zoonotic and emerging. The models confirmed what many experts have been saying: human activity, including human-caused climate change, is a major factor in the evolution and spread of both new and existing diseases.

The research could help scientists predict where and when the next pandemic will arise, but it is also a warning that nations will need to halt the destruction of natural habitats.

“Geodemography, environment and societal characteristics”

Published on March 16, “Geodemography, environment and societal characteristics drive the global diversity of emerging, zoonotic and human pathogens” was authored by Dr. Balbir B Singh, Professor Michael Ward and Associate Professor Navneet Dhand, with the backing of the University of Sydney. The study was published in the international journal “Transboundary and Emerging Diseases.”

The study focused on human diseases (“previously reported infectious human pathogens”), zoonotic diseases (“those diseases and infections which are naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and man”) and emerging diseases (pathogens “that have appeared in a human population for the first time or have occurred previously but are increasing in incidence or expanding into areas where they have not previously been reported, usually over the last 20 years”).

The research used data from 224 countries and 335 emerging infectious disease (EID) events (“defined as those caused by newly evolved strains of pathogens such as multi‐drug‐resistant pathogens or pathogens that have recently entered human populations for the first time or pathogens which have recently increased in incidence”) from 1940 to 2004.

With the data, the researchers examined what role geodemographic (where human populations live), environmental and social factors played in the increasing diversity of various diseases. The greater diversification of diseases leads to a higher likelihood of human infection and resulting pandemics (think of the variety of coronaviruses, including COVID-19).

Calling the need to understand these diseases and their spread “a global priority,” the authors warn that this understanding is “essential to inform disease control and mitigation and to predict the next zoonotic pandemic.”

Conclusions of the University of Sydney study

In their conclusion, the authors state, “We found human population density, land area, mean annual temperature (average) and human development index value [i.e., the social and economic development of countries] to be associated with the overall diversity of human, emerging and zoonotic pathogens.”

The research determined that different global regions are at greater risk due to these factors, with both the US and Australia being among the countries having the highest level of zoonotic diversity.

The countries that were most likely to have higher diversity in zoonotic pathogens (a category that includes COVID-19, HIV/AIDS and Ebola) were those “in a longitude range of −100° to −30.0° (North and South American countries) and having high human population density.”

Greater forest area was also a leading factor in the diversity of zoonotic disease.

In addition to land area and human population density (leading factors in the diversity of all three disease types), greater economic activity was a main factor in the diversity of emerging diseases. Furthermore, the diversity of human diseases was predicted by those three factors as well as higher health expenditures, mean annual temperatures and rainfall.

The US was categorized as having the highest level of diversity for all three types of diseases. China, Brazil, India and Europe contain high to moderately high diversity levels of both human and emerging diseases.

Looking to the future

As nations prepare for the next pandemic – something experts say is inevitable – information like that provided by this research can help governments and businesses better recognize the underlying factors.

“Our analysis suggests sustainable development is not only critical to maintaining ecosystems and slowing climate change; it can inform disease control, mitigation, or prevention,” Professor Ward explained. “Due to our use of national-level data, all countries could use these models to inform their public health policies and planning for future potential pandemics.”

Population density and proximity to forested areas are two of the leading factors in the spread of disease, particularly zoonotic diseases. The potential risks that zoonotic diseases represent for humans is something that should be considered as nations continue to chip away at natural environments.

“As the human population increases,” Associate Professor Dhand warns, “so does the demand for housing. To meet this demand, humans are encroaching on wild habitats. This increases interactions between wildlife, domestic animals and human beings which increases the potential for bugs to jump from animals to humans.”

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()