Do we have an answer to the Tully monster question?

This "monster" was a fish discovered about 70 years ago and has puzzled people since then.

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

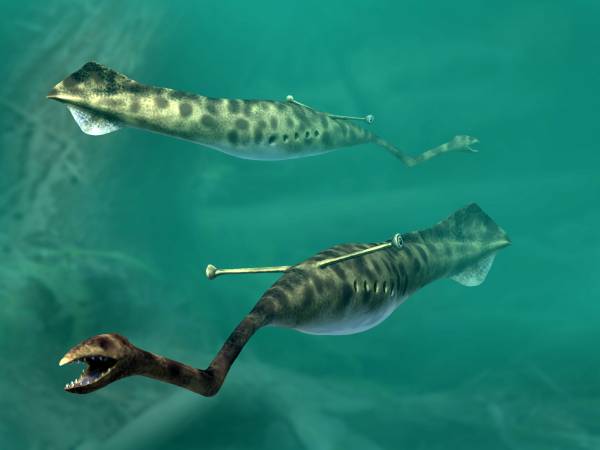

Have you heard of the Tully monster? This "monster" was a fish discovered about 70 years ago and has puzzled people since then. How? Well, paleontologists couldn't tell if it was a vertebrate or an invertebrate, and the science community has gone back and forth about it this whole time.

The Tully monster lived around 300 million years ago, and its fossils were found in Illinois, in the Mazon Creek fossil bed, which used to be underwater. Just 15 centimeters long (6 inches) and definitely a weirder-looking fish, this sea creature's anatomy just couldn't really be classified. With its soft body, similar to jellyfish, the fossil didn't show any evidence of vertebrae, but that's not to say it didn't have it. Also, researchers couldn't figure out its lineage to get an idea. Then, in 2016, some researchers determined that the monster's gut-like structure is a notochord, which is kind of like an almost spine, making the monster a vertebrate.

But the jury was still out.

Now, researchers from the University of Tokyo are saying they've figured out exactly what's going on with this fish and have found characteristics linked to invertebrate identity.

"Based on multiple lines of evidence, the vertebrate hypothesis of the Tully monster is untenable," said paleontologist Tomoyuki Mikami who worked with the University of Tokyo during the study that was published in Palaeontology. "The most important point is that the Tully monster had segmentation in its head region that extended from its body. This characteristic is not known in any vertebrate lineage, suggesting a nonvertebrate affinity."

They figured this out using 3D imaging technology. The research team looked at over 150 fossilized Tully monsters and more than 70 other types of animal fossils from Illinois. Because of the way that fossils in that area were preserved, they often don't form correctly because more sediment piles on top of them. With a 3D laser scanner, the team could make its own maps of the fossils that showed small surface irregularities via color-coded variation (the same tech used to study dino footprints). And with that, the 3D map data showed that the monster's "vertebrate" features aren't consistent with those of other vertebrates.

So now, researchers are convinced the Tully wasn't a vertebrate – but now they have to figure out which group of organisms it does belong to.

Comments ()