QAnon will not disappear even if President Trump loses reelection. Here’s why

A few minutes every morning is all you need.

Stay up to date on the world's Headlines and Human Stories. It's fun, it's factual, it's fluff-free.

While QAnon has intricately linked its fate (and prophetic claims) to the success of Trump as president, there is much to suggest the movement can sustain itself long after his presidency ends.

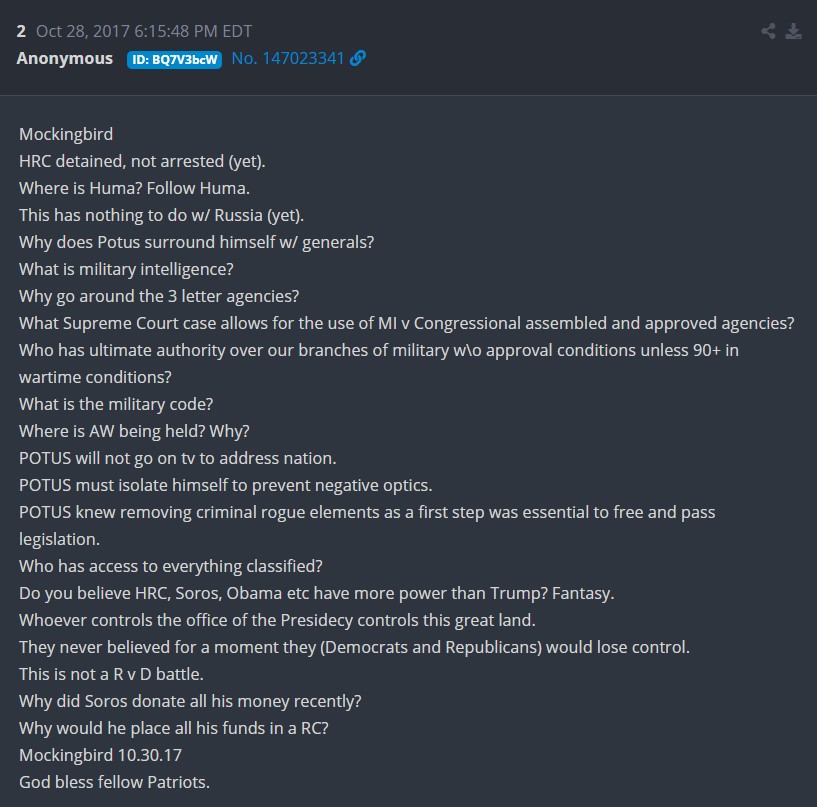

October 28, 2017 could turn out to be a turning point in history, at least if the adherents of the QAnon movement are right. That is the date a mysterious figure known only as “Q” first made his presence known with two 4chan posts. In one, the anonymous figure assured, “Whoever controls the office of the Presidecy [sic] controls this great land.”

The first two so-called QDrops were focused on President Donald Trump and “HRC” (Hillary Rodham Clinton). Q, whoever it might be, preaches a reality in which Clinton, the Democrats and their allies in the “deep state” are at war with Trump. Trump’s allies in this fight are anyone who publicly supports him, but Trump is the center of the QAnon universe.

There are worries Trump will refuse to concede if he loses the election and will attempt to hold onto power. Others are skeptical of such a scenario, especially if election polling is accurate and Trump is soundly defeated by former Vice President Joe Biden. In that case, not only would Trump no longer be president, QAnon would lose its focal point.

While QAnon has intricately linked its fate (and prophetic claims) to the success of Trump as president, there is much to suggest the movement can sustain itself long after his presidency ends. With its focus on Satanic cabals and child sex trafficking, experts believe the movement will morph and adapt to suit whatever political reality comes next.

The politics of QAnon

Taylor Dotson, an Associate Professor of Social Science at New Mexico Tech, spoke with TMS about the longevity of the movement. Dotson characterizes the movement as one based on populism, with its “belief that corrupt elites are silencing the voice of ‘the people.’” Trump, who has repeatedly stoked fears over voter fraud, often plays into this belief.

Even if Trump loses the election, Dotson believes, the QAnon movement will continue as “a political movement or at least a set of conspiracy theories about politics.”

Dotson states, “the exact form of the claims will likely evolve. We should expect these kinds of beliefs about the political ‘deep state’ to persist so long as trust in government remains so low and that the majority of Americans believe that politicians ‘don’t care what people like them think.’”

He doubts QAnon can sustain itself in the long-term the way other conspiracy theories, such as belief in the Illuminati, continue on, specifically because Trump is so central to the movement. Political conspiracy theories like QAnon, however, may be here to stay.

“Whether we continue to see mass conspiracy theory movements or not,” Dotson warns, “will depend on what our political system looks like and whether it is responsive to citizens’ needs, meets emerging crises head on, and is transparent and accountable.”

One relevant historical analogy is the John Birch Society, a conservative political organization that opposes communism but has also been said to “adhere to extreme anti-government doctrines.”

In 1964, JBS strongly supported the Republican nominee for president, Barry Goldwater. After Goldwater’s loss, Dotson explains, JBS continued on, “only losing influence because of changing American attitudes about communism during the Vietnam War and the society’s leader’s decision to smear Dwight D. Eisenhower as a secret communist.”

In other words, the once-influential political movement moved too far afield of mainstream American thought.

Infiltrating American life

QAnon’s niche belief system – which, among other things, claims celebrities like Tom Hanks and Oprah are part of a Satanic child sex trafficking cabal – is hardly mainstream. It is, however, gaining influence, both by obscuring its origins and by taking advantage of concerns over child sexual abuse through movements like the #SaveTheChildren campaign.

There are two sides to the QAnon phenomenon – the political and the spiritual – and while they are intertwined, they also allow for distinct threads that could exist on their own.

In fact, QAnon’s forced association with efforts to address sex trafficking (and its related religious undertones) is one way the movement is likely to sustain its influence even if Trump loses.

Barna William Donovan, a professor of communication and media culture at Saint Peter’s University, told TMS that, like Dotson, he believes QAnon can survive without Trump. Donovan, who is the author of “Conspiracy Films: A Tour of Dark Places in the American Conscious,” believes the movement’s moralistic undercurrent will provide it longevity.

“At the core of [QAnon],” Donovan explains, “is the idea that there is a massive Satanic pedophile cabal running the world and Donald Trump is waging a secret battle against this invisible empire of evil. So, if Trump is defeated, QAnon will see this as a sign that the Satanic cabal is even bigger and stronger and QAnon members need to dedicate themselves to fighting this force even harder.”

Donovan also thinks QAnon distinguishes itself from other recent political movements, such as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street, because it mixes the political with the religious.

“I could see QAnon’s future as more of a quasi-religious movement since they don’t appear to have any focused, coherent political aim,” he states. “QAnon does not have any specific political identity other than a general right-wing, anti-government fear of individual rights being encroached upon.

“QAnon’s reason for existing is its Satanic conspiracy theory and its Apocalyptic narrative of a coming showdown between the forces of good and evil. The future of the movement, I think, would be to attract those inclined towards fundamentalist, ultraorthodox Christian worldviews, especially those on the Christian fringes who see the culture wars directly threatening their faith.”

Something even darker?

“The greatest threat QAnon poses to this culture,” Donovan believes, “is its attack on the very idea of an objective consensus reality, for one. This movement poses a grave threat in its rejection of all authority figures, all ideas of expertise.”

Jonathan Lockwood, a political consultant, envisions an even more dire evolution for QAnon as its political and cultural influence grows.

“QAnon is becoming a terrorist organization and needs to be handled,” Lockwood told TMS. “The lies and mythology in QAnon [are] exploitative of real victims of human trafficking and other heinous realities.”

Taina Bien-Aimé, the Executive Director of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW), who spoke with TMS earlier this year, voiced a similar concern: “Certainly conspiracies theories are extremely dangerous to our work, but also what’s dangerous is the narrative around it that really distorts people’s understanding of human trafficking and how to address it.”

Lockwood warns that much of QAnon relies on well-established antisemitic beliefs and tropes. Specifically, he mentions the connection between QAnon theories and “The Protocols of The Elders of Zion,” which the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum calls “the most notorious and widely distributed antisemitic publication of modern times.”

One clear example of anti-Semitism within the QAnon mythology is its attacks on George Soros, the Jewish billionaire often derided by right-wing critics for his financial support of liberal causes. Soros is a frequent subject of conspiracy theories, but Q’s focus on the philanthropist (he is mentioned by name in the second QDrop) relies heavily on the myth that Jews secretly control the world.

The word “cabal” (i.e. a secret organization or plot), which has frequently appeared in QDrops, has a long history of being used as a code word for Jews.

Trump, himself, has on multiple occasions used imagery and phrases that have well-established antisemitic associations. He has also utilized white supremacist talking points.

What could this appeal to extremist views mean for the future of QAnon?

“The danger in QAnon,” Lockwood argues, “is that real problems that exist in society, like human trafficking, are being used as political weapons against political opponents of this lawless, evil president. We’ve seen assassination plots, kidnappings and violent uprisings and my fear is that it will not only continue but will become more intense and violent.”

Can the minds of QAnon followers be changed?

It is common for critics of the movement to say QAnon is a cult. While there are those who contend that is an unfair comparison, there are clear comparison points, including adherence to extreme beliefs and nearly spiritual reverence for Trump. So, what happens if these “spiritual” QAnon followers are faced with disappointment on (or after) November 3?

There is an illuminating historical precedent: the birth of Seventh Day Adventism. That Christian denomination is rooted in the Millerites, a group of 19th-century followers of an American prophet named William Miller. Miller predicted Jesus Christ would return on October 22, 1844. Alas, October 22 came and went without Christ’s second coming, leading the day to be called “The Great Disappointment.”

Nonetheless, the roots of Adventism were established that day. Millerites adapted their beliefs so that, even though Miller’s initial prophecy did not come true, their faith remained unbroken.

So, if Trump is defeated at the polls and the promised “storm” does not come, what happens next?

“Some people no doubt will fall away from conspiracy theories altogether,” Professor Dotson suggests, but that won’t necessarily be the most common reaction. “More broadly the following of these theories isn’t so much about whether predictions pan out. Although there is an underlying motivation to look for evidence that the theories are right, conspiracy theories aren’t so easily disproved.”

Professor Donovan agrees, saying QAnon followers could just latch onto another belief system: “Research shows that people who are staunch, committed believers in at least one conspiracy theory will also be very open-minded to numerous other such theories.”

Donovan adds, “History also shows that people who are drawn to belief systems on the fringes of society will continue to seek out similar belief systems even after breaking away from one group.”

The future of QAnon

Despite these concerns, Dotson is worried about our collective response to the movement, especially when it comes to trying to contain its spread.

“I don’t believe that banning groups from social media platforms will smother them out,” he says, “but only increase the pressure, though it should also reduce recruiting. As Richard Hofstadter noted in his classic essay on the ‘Paranoid Style in American Politics,’ exclusion only feeds the belief among conspiracy theorists that they are a persecuted minority.”

So, does that mean there is nothing to be done and QAnon is here to stay? Probably not in its current form, Dotson predicts, but conspiracy theories aren’t going away, especially not as the world faces catastrophic issues like pandemics and climate change.

“While the name QAnon might eventually disappear from the cultural conversation, its effects,” Donovan thinks, “will be around for decades to come. This movement represents a home for the angry and disaffected. It represents a home for those who aggressively reject all facts, data, and science, who reject the very concepts of proof, truth, and standards of evidence if they contradict the believer’s world views.”

“I believe that the impacts of what we are seeing unfold in 2020,” Lockwood concludes, “will either expand and become more insane and dangerous, or there will be a swift and stark condemnation of this kind of behavior from the public-at-large. I believe in the power of America and the American people more than I do the power of Trump and the social engineering of QAnon.”

Have a tip or story? Get in touch with our reporters at tips@themilsource.com

Comments ()